Tumor necrosis factor

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF, cachexin, or cachectin; formerly known as tumor necrosis factor alpha, TNFα [without a dash in between] or TNF-α [with a dash][5][6]) is a cytokine and member of the TNF superfamily, which consists of various transmembrane proteins with a homologous TNF domain. It is the first cytokine to be described as an adipokine as secreted by adipose tissue.[7]

TNF signaling occurs through two receptors: TNFR1 and TNFR2.[8][9] TNFR1 is constitutively expressed on most cell types, whereas TNFR2 is restricted primarily to endothelial, epithelial, and subsets of immune cells.[8][9] TNFR1 signaling tends to be pro-inflammatory and apoptotic, whereas TNFR2 signaling is anti-inflammatory and promotes cell proliferation.[8][9] Suppression of TNFR1 signaling has been important for treatment of autoimmune diseases,[10] whereas TNFR2 signaling promotes wound healing.[9]

TNF-α exists as a transmembrane form (mTNF-α) and as a soluble form (sTNF-α). sTNF-α results from enzymatic cleavage of mTNF-α,[11] by a process called substrate presentation. mTNF-α is mainly found on monocytes/macrophages where it interacts with tissue receptors by cell-to-cell contact.[11] sTNF-α selectively binds to TNFR1, whereas mTNF-α binds to both TNFR1 and TNFR2.[12] TNF-α binding to TNFR1 is irreversible, whereas binding to TNFR2 is reversible.[13]

The primary role of TNF is in the regulation of immune cells. TNF, as an endogenous pyrogen, is able to induce fever, apoptotic cell death, cachexia, and inflammation, inhibit tumorigenesis and viral replication, and respond to sepsis via IL-1 and IL-6-producing cells. Dysregulation of TNF production has been implicated in a variety of human diseases including Alzheimer's disease,[14] cancer,[15] major depression,[16] psoriasis[17] and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[18] Though controversial, some studies have linked depression and IBD to increased levels of TNF.[19][20]

As an adipokine, TNF promotes insulin resistance, and is associated with obesity-induced type 2 diabetes.[7] As a cytokine, TNF is used by the immune system for cell signaling. If macrophages (certain white blood cells) detect an infection, they release TNF to alert other immune system cells as part of an inflammatory response.[7] Certain cancers can cause overproduction of TNF. TNF parallels parathyroid hormone both in causing secondary hypercalcemia and in the cancers with which excessive production is associated. Under the name tasonermin, TNF is used as an immunostimulant drug in the treatment of certain cancers. Drugs that counter the action of TNF are used in the treatment of various inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

History

[edit]Discovery

[edit]In the 1890s, William B. Coley, based on anecdotes of cancer patients being cured by sudden attacks of erysipelas, theorized that bacterial infections had a beneficial effect against tumors, particularly sarcomas. Coley was able to successfully treat cancer patients by injecting them with a mixture of bacterial toxins from heat-sterilized Streptococcus and Bacillus prodigiosus in and around the tumors, causing the tumors to hemorrhage. However, the effectiveness of this treatment was inconsistent and repeated injections caused severe side effects such as chills and fevers, causing the treatment to be discontinued.[21]

In the 1930s and 1940s, Shear et al. isolated the active tumor-hemorrhaging agent from the bacterial toxins of Escherichia coli and Serratia marcescens. They demonstrated that this agent, endotoxin, when injected into mice with sarcomas, could inhibit tumor growth or cause tumor regression.[22] However, tumor regression was highly variable, with smaller doses of endotoxin often having more potency than larger doses, or entire batches of mice being resistant to the endotoxin.[23]

In 1975, Elizabeth Carswell and Lloyd Old et al. investigated the tumor-killing properties of endotoxin by extracting serum from donor mice injected with endotoxin, and injecting the serum into recipient mice carrying transplanted sarcomas. They discovered that donor mice infected with Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG), upon exposure to endotoxin, produced serum that caused the tumors to hemorrhage in the recipient mice. The serum of BCG-infected donor mice did not contain residual endotoxins, leading the authors to conclude that the serum contained a separate cytotoxic factor, termed Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF). Since BCG-infected mice had enlarged spleens due to an increased production of macrophages, the authors deduced that TNF was released by macrophages upon exposure to endotoxins.[24]

In addition to causing sarcomas to hemorrhage in vivo, TNF was also cytotoxic to L-929 cells, a transformed cell line, in vitro. Cytotoxicity to L-929 cells in vitro became the standard technique for detecting TNF. [25] TNF was cytotoxic to cancerous and transformed cell lines, but not to normal, untransformed cell lines, raising hopes that it could be used as a cancer therapy. [24]

Isolation, Sequencing, and Expression

[edit]In August 1984, Bharat Aggarwal et al. at Genentech purified and characterized human TNF. The TNF was produced by culturing HL-60, a human cell line, with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), a phagocyte stimulant similar to endotoxin. The TNF was purified using controlled pore glass beads, DEAE chromatography, Mono Q chromatography, and reversed-phase HPLC. TNF purified using reversed-phase HPLC was determined to have a molecular weight of 17,000 kDa by SDS-PAGE, whereas TNF purified using TSK-HPLC under nondenaturing conditions was determined to have an approximate molecular weight of 45,000 kDa, suggesting that TNF naturally exists as an oligomer. The TNF amino acid sequence was determined using Edman degradation, revealing a sequence of 157 amino acids with significant homology to the amino acid sequence of lymphotoxin. [26]

In that same month, Pennica et al, also at Genentech, sequenced the cDNA of human TNF. A cDNA library was constructed from the mRNA of HL-60 cells induced by PMA. A 42-base long DNA probe, constructed by guessing the codons of a portion of the TNF amino acid sequence, was used to screen the cDNA library. The matching cDNA was sequenced, revealing a presequence of 76 amino acids followed by the 157 amino acids of mature TNF. The authors deduced that TNF is first synthesized into a larger precursor form containing a signal peptide, before being processed and released as a smaller mature form. The authors also synthesized TNF in e coli and verified its cytotoxicity against L-929 cells in vitro and against mouse sarcomas in vivo. [27]

Physiological Effects

[edit]In June 1981, Ian A. Clark et al. found that healthy mice infected with Plasmodium vinckei, a malaria-causing parasite, upon exposure to endotoxin, developed malaria-like symptoms such as liver damage, hypoglycemia, and blood clotting, while also releasing mediators including TNF. Uninfected mice did not release these mediators when injected with endotoxin. These results, combined with evidence of endotoxins in the serum of malaria patients, led the authors to propose that mediators such as TNF are present in acute malaria infections, and that they play a role in causing malaria symptoms. [28]

In 1985, Kevin J. Tracy, Ian Milsark, and Anthony Cerami found that mice immunized from TNF via TNF antiserum were resistant to the lethal effects of endotoxin, indicating that TNF is one of the mediators of endotoxin lethality. [29] In 1986, this was confirmed by Kevin J. Tracy and Bruce Beutler, when they demonstrated that mice injected with TNF exhibited common symptoms of endotoxin poisoning, such as hypotension, metabolic acidosis, hemoconcentration, and death. [30]

In 1991, Michael Goodman demonstrated that mice injected with TNF released increased levels of tyrosine and 3-methyl-L-histidine in their skeletal muscles, indicating that TNF induces muscle breakdown. [31] In 1996, Stefferl et al. demonstrated that mice injected with mouse TNF develop fevers, definitively demonstrating that TNF is a pyrogen. Previous studies showed inconclusive results due to the use of human TNF, rather than mouse TNF, on mice. [32]

The observation that TNF induces wasting and endotoxic shock led to rethinking about its potential role as a cancer therapy. [25]

Identification with Cachectin

[edit]In September 1981, Masanobu Kawakami and Anthony Cerami investigated the tendency of bacteria endotoxins to induce hypertriglyceridemia, caused by a deficiency of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), when administered to animals. They extracted serum from donor mice injected with endotoxin and injected the serum into recipient mice. They discovered that endotoxin-resistant recipient mice had decreased LPL activity after receiving the serum of endotoxin-treated mice, even though their LPL activities were not markedly reduced when injected with endotoxin directly. The authors also discovered that exudate cells, consisting mostly of macrophages, when incubated with endotoxins, produced a medium that lowered LPL activity when injected into mice. The authors deduced that hypertriglyceridemia was caused by a mediating factor, termed cachectin, secreted by exudate cells in response to endotoxins. [33]

In 1985, Beutler et al. demonstrated that mouse cachectin has similar cytotoxicity against L-929 cells as TNF, as well as a near identical N-terminal amino acid sequence to human TNF, indicating that cachectin and TNF were the same protein. Since cachectin (now TNF) is known to suppress the biosynthesis of a specific protein, lipoprotein lipase, the authors deduced that TNF's cytotoxic mechanism operated in a similar way. [34]

Name Changes

[edit]In 1968, lymphotoxin, a cytotoxin secreted by lymphocytes, was discovered. Both TNF and lymphotoxin were detected based on their ability to kill L-929 cells, were able to bind to the two known TNF receptors, TNFRI and TNFRII, and shared significant genetic and amino acid homology. The similarities between TNF and lymphotoxin led to the unofficial renaming of TNF to TNF-α and lymphotoxin to TNF-β, with the published rationale being that they are detected with the same in vitro assays. [25]

In 1993, lymphotoxin, which is not a transmembrane protein, was discovered to be present on the cell membrane by forming a complex with a separate transmembrane glycoprotein, termed lymphotoxin-β. [35] Lymphotoxin was also discovered to play a critical role in the development of lymphoid organs, distinguishing its biological function from TNF. As a result of these developments, TNF-β was renamed to lymphotoxin-α, and TNF-α was renamed back to TNF. [25]

Gene

[edit]The human TNF gene was cloned in 1985.[36] It maps to chromosome 6p21.3, spans about 3 kilobases and contains 4 exons. The last exon shares similarity with lymphotoxin alpha (LTA, once named as TNF-β).[37] The three prime untranslated region (3'-UTR) of TNF contains an AU-rich element (ARE).

Structure

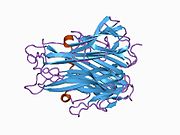

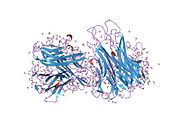

[edit]TNF is primarily produced as a 233-amino acid-long type II transmembrane protein arranged in stable homotrimers.[38][39] From this membrane-integrated form the soluble homotrimeric cytokine (sTNF) is released via proteolytic cleavage by the metalloprotease TNF alpha converting enzyme (TACE, also called ADAM17).[40] The soluble 51 kDa trimeric sTNF tends to dissociate at concentrations below the nanomolar range, thereby losing its bioactivity. The secreted form of human TNF takes on a triangular pyramid shape, and weighs around 17-kDa. Both the secreted and the membrane bound forms are biologically active, although the specific functions of each is controversial. But, both forms do have overlapping and distinct biological activities.[41]

The common house mouse TNF and human TNF are structurally different.[42] The 17-kilodalton (kDa) TNF protomers (185-amino acid-long) are composed of two antiparallel β-pleated sheets with antiparallel β-strands, forming a 'jelly roll' β-structure, typical for the TNF family, but also found in viral capsid proteins.

Cell signaling

[edit]TNF can bind two receptors, TNFR1 (TNF receptor type 1; CD120a; p55/60) and TNFR2 (TNF receptor type 2; CD120b; p75/80). TNFR1 is 55-kDa and TNFR2 is 75-kDa.[43] TNFR1 is expressed in most tissues, and can be fully activated by both the membrane-bound and soluble trimeric forms of TNF, whereas TNFR2 is found typically in cells of the immune system, and responds to the membrane-bound form of the TNF homotrimer. As most information regarding TNF signaling is derived from TNFR1, the role of TNFR2 is likely underestimated. At least partly because TNFR2 has no intracellular death domain, it shows neuroprotective properties.[44]

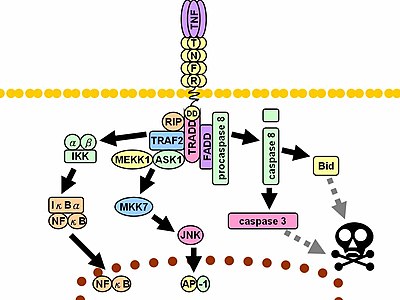

Upon contact with their ligand, TNF receptors also form trimers, their tips fitting into the grooves formed between TNF monomers. This binding causes a conformational change to occur in the receptor, leading to the dissociation of the inhibitory protein SODD from the intracellular death domain. This dissociation enables the adaptor protein TRADD to bind to the death domain, serving as a platform for subsequent protein binding. Following TRADD binding, three pathways can be initiated.[45][46]

- Activation of NF-κB: TRADD recruits TRAF2 and RIP. TRAF2 in turn recruits the multicomponent protein kinase IKK, enabling the serine-threonine kinase RIP to activate it. An inhibitory protein, IκBα, that normally binds to NF-κB and inhibits its translocation, is phosphorylated by IKK and subsequently degraded, releasing NF-κB. NF-κB is a heterodimeric transcription factor that translocates to the nucleus and mediates the transcription of a vast array of proteins involved in cell survival and proliferation, inflammatory response, and anti-apoptotic factors.

- Activation of the MAPK pathways: Of the three major MAPK cascades, TNF induces a strong activation of the stress-related JNK group, evokes moderate response of the p38-MAPK, and is responsible for minimal activation of the classical ERKs. TRAF2/Rac activates the JNK-inducing upstream kinases of MLK2/MLK3,[47] TAK1, MEKK1 and ASK1 (either directly or through GCKs and Trx, respectively). SRC- Vav- Rac axis activates MLK2/MLK3 and these kinases phosphorylate MKK7, which then activates JNK. JNK translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription factors such as c-Jun and ATF2. The JNK pathway is involved in cell differentiation, proliferation, and is generally pro-apoptotic.

- Induction of death signaling: Like all death-domain-containing members of the TNFR superfamily, TNFR1 is involved in death signaling.[48] However, TNF-induced cell death plays only a minor role compared to its overwhelming functions in the inflammatory process. Its death-inducing capability is weak compared to other family members (such as Fas), and often masked by the anti-apoptotic effects of NF-κB. Nevertheless, TRADD binds FADD, which then recruits the cysteine protease caspase-8. A high concentration of caspase-8 induces its autoproteolytic activation and subsequent cleaving of effector caspases, leading to cell apoptosis.

The myriad and often-conflicting effects mediated by the above pathways indicate the existence of extensive cross-talk. For instance, NF-κB enhances the transcription of C-FLIP, Bcl-2, and cIAP1 / cIAP2, inhibitory proteins that interfere with death signaling. On the other hand, activated caspases cleave several components of the NF-κB pathway, including RIP, IKK, and the subunits of NF-κB itself. Other factors, such as cell type, concurrent stimulation of other cytokines, or the amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can shift the balance in favor of one pathway or another.[citation needed] Such complicated signaling ensures that, whenever TNF is released, various cells with vastly diverse functions and conditions can all respond appropriately to inflammation.[citation needed] Both protein molecules tumor necrosis factor alpha and keratin 17 appear to be related in case of oral submucous fibrosis[49]

In animal models TNF selectively kills autoreactive T cells.[50]

There is also evidence that TNF-α signaling triggers downstream epigenetic modifications that result in lasting enhancement of pro-inflammatory responses in cells.[51][52][53][54]

Enzyme regulation

[edit]This protein may use the morpheein model of allosteric regulation.[55]

Clinical significance

[edit]TNF was thought to be produced primarily by macrophages,[56] but it is produced also by a broad variety of cell types including lymphoid cells, mast cells, endothelial cells, cardiac myocytes, adipose tissue, fibroblasts, and neurons.[57][unreliable medical source?] Large amounts of TNF are released in response to lipopolysaccharide, other bacterial products, and interleukin-1 (IL-1). In the skin, mast cells appear to be the predominant source of pre-formed TNF, which can be released upon inflammatory stimulus (e.g., LPS).[58]

It has a number of actions on various organ systems, generally together with IL-1 and interleukin-6 (IL-6):

- On the hypothalamus:

- Stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by stimulating the release of corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH)

- Suppressing appetite

- Fever

- On the liver: stimulating the acute phase response, leading to an increase in C-reactive protein and a number of other mediators. It also induces insulin resistance by promoting serine-phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), which impairs insulin signaling

- It is a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils, and promotes the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, helping neutrophils migrate.

- On macrophages: stimulates phagocytosis, and production of IL-1 oxidants and the inflammatory lipid prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

- On other tissues: increasing insulin resistance. TNF phosphorylates insulin receptor serine residues, blocking signal transduction.

- On metabolism and food intake: regulates bitter taste perception.[59]

A local increase in concentration of TNF will cause the cardinal signs of Inflammation to occur: heat, swelling, redness, pain and loss of function.

Whereas high concentrations of TNF induce shock-like symptoms, the prolonged exposure to low concentrations of TNF can result in cachexia, a wasting syndrome. This can be found, for example, in cancer patients.

Said et al. showed that TNF causes an IL-10-dependent inhibition of CD4 T-cell expansion and function by up-regulating PD-1 levels on monocytes which leads to IL-10 production by monocytes after binding of PD-1 by PD-L.[60]

The research of Pedersen et al. indicates that TNF increase in response to sepsis is inhibited by the exercise-induced production of myokines. To study whether acute exercise induces a true anti-inflammatory response, a model of 'low grade inflammation' was established in which a low dose of E. coli endotoxin was administered to healthy volunteers, who had been randomised to either rest or exercise prior to endotoxin administration. In resting subjects, endotoxin induced a 2- to 3-fold increase in circulating levels of TNF. In contrast, when the subjects performed 3 hours of ergometer cycling and received the endotoxin bolus at 2.5 h, the TNF response was totally blunted.[61] This study provides some evidence that acute exercise may inhibit TNF production.[62]

In the brain TNF can protect against excitotoxicity.[44] TNF strengthens synapses.[8] TNF in neurons promotes their survival, whereas TNF in macrophages and microglia results in neurotoxins that induce apoptosis.[44]

TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations are elevated in obesity.[63][64][65] Use of monoclonal antibodies against TNF-α is associated with increases rather than decreases in obesity, indicating that inflammation is the result, rather than the cause, of obesity.[65] TNF and IL-6 are the most prominent cytokines predicting COVID-19 severity and death.[7]

TNFα in Liver Fibrosis

TNFα mediates the inflammation that activates resident Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSCs) into the fibrogenic myofibroblasts that are largely responsible for liver fibrosis. However, whereas TNF receptor 1 knock-out mice demonstrate reduced fibrosis, TNFα can also suppress collagen α1(I) gene expression in fibroblasts in vitro, raising questions in regard to the complexity of its role in liver fibrosis.[66]

While TNFα treatment suppresses collagen α1 gene expression, apoptosis, and proliferation in activated HSCs in vitro, an activity that should ameliorate fibrosis, it has also been shown to inhibit apoptosis in activated HSCs, an activity which should, in principle, induce fibrosis.[67] Specifically, TNFα produced by hepatic macrophages is known to support the survival of HSCs, the source of hepatic myofibroblasts.[68] TNFα is therefore believed to promote liver fibrosis through its pro-survival effect, despite its pleiotropic effects on HSCs.[69]

Yet another way TNFα contributes to the worsening of liver fibrosis is by stimulating the production of TGF-β by hepatocytes and TIMP1 by hepatocytes and HSCs.[70]

It should furthermore be noted that CCR9+ macrophages, which play an essential role in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis, are TNFα-dependent. When TNFα is attenuated using an anti-TNFα antibody, hepatic HSCs are not activated by CCR9+ macrophages.[71]

TNFα in NAFLD

TNFα has a dual role in the development of NAFLD. Firstly, it is released among other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-1β, in response to the increased signaling from NF-κB during steatosis. TNFα then participates in the recruitment of Kuppfer cells, which increase inflammation and lead to the development of NASH.[72]

Secondly, the binding of TNFα to TNFα receptor 1 (TNFR1) facilitates insulin resistance, a known contributor to NAFLD progression, by suppressing insulin signaling.[73] Following the binding of TNF-α to TNFR1, intracellular c-JUN N terminal kinase (JNK) and IkB kinase (IKK) signals are activated, and the phosphorylation of JNK (p-JNK) and IKK1/1KK2 further attenuate insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1). The phosphorylation of IRS-1 leads to the suppression of insulin signaling and, subsequently, to insulin resistance.[74] Indeed, a study has demonstrated that blocking TNFR1 protected Wistar rats from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance.[74]

TNFR1 inhibition has been suggested as a possible therapy for NAFLD. A high-fat diet (HFD) mouse model of NAFLD has been used to demonstrate that the use of an anti-TNFR1-antibody can reduce liver steatosis and triglyceride content, as well as the activation of downstream target genes of lipogenesis. Insulin resistance likewise improved in these mice as a result of the reduced activation of MAP kinase MKK7 and its downstream target JNK.[75]

It is additionally thought that TNFα increases the production of MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1). MCP-1 is known to be overexpressed in obesity and is believed to be responsible for the recruitment of macrophages into adipose tissue and contribute to insulin resistance.[76] The production of MCP-1 increases in primary hepatocytes exposed to TNFα; TNF-α stimulates Mcp1 gene transcription by activating the Akt/PKB pathway.[77]

The dual role of TNFα in the development of NAFLD is counteracted by the anti-inflammatory action of adiponectin, whose production is impaired in metabolic syndrome.[70]

TNFα is, therefore, thought to play a deleterious role in the progression of NAFLD to NASH and cirrhosis.

Pharmacology

[edit]TNF promotes the inflammatory response, which, in turn, causes many of the clinical problems associated with autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa and refractory asthma. These disorders are sometimes treated by using a TNF inhibitor. This inhibition can be achieved with a monoclonal antibody such as infliximab (Remicade) binding directly to TNF, adalimumab (Humira), certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) or with a decoy circulating receptor fusion protein such as etanercept (Enbrel) which binds to TNF with greater affinity than the TNFR.[78]

On the other hand, some patients treated with TNF inhibitors develop an aggravation of their disease or new onset of autoimmunity. TNF seems to have an immunosuppressive facet as well. One explanation for a possible mechanism is this observation that TNF has a positive effect on regulatory T cells (Tregs), due to its binding to the tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2).[79]

Anti-TNF therapy has shown only modest effects in cancer therapy. Treatment of renal cell carcinoma with infliximab resulted in prolonged disease stabilization in certain patients. Etanercept was tested for treating patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer showing prolonged disease stabilization in certain patients via downregulation of IL-6 and CCL2. On the other hand, adding infliximab or etanercept to gemcitabine for treating patients with advanced pancreatic cancer was not associated with differences in efficacy when compared with placebo.[80]

Interactions

[edit]TNF has been shown to interact with TNFRSF1A.[81][82]

Nomenclature

[edit]Because LTα is no longer referred to as TNFβ,[83] TNFα, as the previous gene symbol, is now simply called TNF, as shown in HGNC (HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee) database.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c ENSG00000230108, ENSG00000223952, ENSG00000204490, ENSG00000228321, ENSG00000232810, ENSG00000228849, ENSG00000206439 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000228978, ENSG00000230108, ENSG00000223952, ENSG00000204490, ENSG00000228321, ENSG00000232810, ENSG00000228849, ENSG00000206439 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000024401 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Liu CY, Tam SS, Huang Y, Dubé PE, Alhosh R, Girish N, et al. (October 2020). "TNF Receptor 1 Promotes Early-Life Immunity and Protects against Colitis in Mice". Cell Reports. 33 (3): 108275. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108275. PMC 7682618. PMID 33086075.

- ^ Gravallese EM, Monach PA (January 2015). "The rheumatoid joint: Synovitis and tissue destruction.". Rheumatology. Vol. 1 (Sixth ed.). Mosby. pp. 768–784. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-09138-1.00094-2. ISBN 978-0-323-09138-1.

The simplified name TNF is now preferred over the former designation TNF-α because the corresponding term TNF-β, an alternative name for LT, is now obsolete.

- ^ a b c d Sethi JK, Hotamisligil GS (October 2021). "Metabolic Messengers: tumour necrosis factor". Nature Metabolism. 3 (10): 1302–1312. doi:10.1038/s42255-021-00470-z. PMID 34650277. S2CID 238991468.

- ^ a b c d Heir R, Stellwagen D (2020). "TNF-Mediated Homeostatic Synaptic Plasticity: From in vitro to in vivo Models". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 14: 565841. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.565841. PMC 7556297. PMID 33192311.

- ^ a b c d Gough P, Myles IA (2020). "Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptors: Pleiotropic Signaling Complexes and Their Differential Effects". Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 585880. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.585880. PMC 7723893. PMID 33324405.

- ^ Rolski F, Błyszczuk P (October 2020). "Complexity of TNF-α Signaling in Heart Disease". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (10): 3267. doi:10.3390/jcm9103267. PMC 7601316. PMID 33053859.

- ^ a b Qu Y, Zhao G, Li H (2017). "Forward and Reverse Signaling Mediated by Transmembrane Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and TNF Receptor 2: Potential Roles in an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 1675. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01675. PMC 5712345. PMID 29234328.

- ^ Probert L (August 2015). "TNF and its receptors in the CNS: The essential, the desirable and the deleterious effects". Neuroscience. 302: 2–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.038. PMID 26117714.

- ^ Szondy Z, Pallai A (January 2017). "Transmembrane TNF-alpha reverse signaling leading to TGF-beta production is selectively activated by TNF targeting molecules: Therapeutic implications". Pharmacological Research. 115: 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.025. PMID 27888159. S2CID 40818956.

- ^ Swardfager W, Lanctôt K, Rothenburg L, Wong A, Cappell J, Herrmann N (November 2010). "A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer's disease". Biological Psychiatry. 68 (10): 930–941. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.012. PMID 20692646. S2CID 6544784.

- ^ Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ (February 2001). "The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology". Cell. 104 (4): 487–501. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00237-9. PMID 11239407. S2CID 7657797.

- ^ Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. (March 2010). "A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression". Biological Psychiatry. 67 (5): 446–457. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. PMID 20015486. S2CID 230209.

- ^ Victor FC, Gottlieb AB (December 2002). "TNF-alpha and apoptosis: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 1 (3): 264–275. PMID 12851985.

- ^ Brynskov J, Foegh P, Pedersen G, Ellervik C, Kirkegaard T, Bingham A, et al. (July 2002). "Tumour necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme (TACE) activity in the colonic mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease". Gut. 51 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1136/gut.51.1.37. PMC 1773288. PMID 12077089.

- ^ Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ (February 2007). "Controversies surrounding the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a literature review". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 13 (2): 225–234. doi:10.1002/ibd.20062. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30091069. PMID 17206706.

- ^ Bobińska K, Gałecka E, Szemraj J, Gałecki P, Talarowska M (2017). "Is there a link between TNF gene expression and cognitive deficits in depression?". Acta Biochimica Polonica. 64 (1): 65–73. doi:10.18388/abp.2016_1276. PMID 27991935.

- ^ Lundin JI, Checkoway H (September 2009). "Endotoxin and Cancer". Environmental Health Perspectives. 117 (9): 1344–1350. Bibcode:2009EHP...117.1344L. doi:10.1289/ehp.0800439. PMC 225248. PMID 19750096.

- ^ Shear MJ, Perrault A (April 1944). "Chemical Treatment of Tumors. IX. Reactions of Mice with Primary Subcutaneous Tumors to Injection of a Hemorrhage-Producing Bacterial Polysaccharide". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 4 (5): 461–476. Bibcode:1944JNCI....4..461K. doi:10.1093/jnci/4.5.461.

- ^ Shear MJ, Perrault A (August 1943). "Chemical Treatment of Tumors. VI. Method Employed in Determining the Potency of Hemorrhage-Producing Bacterial Preparations". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 4 (1): 99–105. Bibcode:1943JNCI....4...99S. doi:10.1093/jnci/4.1.99.

- ^ a b Carswell EA, Old LJ, Kassel RL, Green S, Fiore N, Williamson B (September 1975). "An endotoxin-induced serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 72 (9): 3666–3670. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.3666C. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.9.3666. PMC 433057. PMID 1103152.

- ^ a b c d Ruddle NH (April 2014). "Lymphotoxin and TNF: How it all began- A tribute to the travelers". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 25 (2): 83–89. Bibcode:2014CaGFR..25...83R. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.02.001.

- ^ Aggarwal BB, Kohr WJ, Hass PE, Moffat B, Spencer SA, Henzel WJ, et al. (February 1985). "Human tumor necrosis factor. Production, purification, and characterization". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 260 (4): 2345–2354. Bibcode:1985JBC...260.2345A. PMID 3871770.

- ^ Pennica D, Nedwin GE, Hayflick JS, Seeburg PH, Derynck R, Palladino MA, et al. (December 1985). "Human tumour necrosis factor: precursor structure, expression and homology to lymphotoxin". Nature. 312 (5996): 724–729. Bibcode:1985N.....312.5996P. doi:10.1038/312724a0. PMID 6392892.

- ^ Clark IA, Virelizier JL, Carswell EA, Wood PR (June 1981). "Possible importance of macrophage-derived mediators in acute malaria". Infection and Immunity. 32 (3): 1058–1066. Bibcode:1981IaI....32.1058C. doi:10.1128/iai.32.3.1058-1066.1981. PMC 351558. PMID 6166564.

- ^ Beutler B, Milsark IW, Cerami AC (August 1985). "Passive immunization against cachectin/tumor necrosis factor protects mice from lethal effect of endotoxin". Science. 229 (4716): 869–871. Bibcode:1985S.....229..869B. doi:10.1126/science.3895437. PMID 3895437.

- ^ Tracey KJ, Beutler B, Lowry SF, Merryweather J, Wolpe S, Milsark IW, et al. (October 1986). "Shock and tissue injury induced by recombinant human cachectin". Science. 234 (4775): 470–474. Bibcode:1986S.....234..470T. doi:10.1126/science.3764421. PMID 3764421.

- ^ Goodman MN (May 1991). "Tumor necrosis factor induces skeletal muscle protein breakdown in rats". American Journal of Physiology. 260 (5 Pt 1): 727–730. Bibcode:1991AJP...260..727G. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.5.E727. PMID 2035628.

- ^ Stefferl A, Hopkins SJ, Rothwell NJ, Luheshi GN (August 1996). "The role of TNF-alpha in fever: opposing actions of human and murine TNF-alpha and interactions with IL-beta in the rat". British Journal of Pharmacology. 118 (8): 1919–1924. Bibcode:1996BJP...118.1919S. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15625.x. PMC 1909906. PMID 8864524.

- ^ Kawakami M, Cerami A (September 1981). "Studies of endotoxin-induced decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 154 (3): 631–639. Bibcode:1981JEM...154..631K. doi:10.1084/jem.154.3.631. PMC 2186462. PMID 7276825.

- ^ Beutler B, Greenwald D, Hulmes JD, Chang M, Pan YC, Mathison J, et al. (August 1985). "Identity of tumour necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin". Nature. 316 (6028): 552–554. Bibcode:1985N.....312..724B. doi:10.1038/316552a0. PMID 2993897.

- ^ Browning JL, Ngam-ek A, Lawton P, DeMarinis J, Tizard R, Chow EP, et al. (March 1993). "Lymphotoxin beta, a novel member of the TNF family that forms a heteromeric complex with lymphotoxin on the cell surface". Cell. 72 (6): 847–856. Bibcode:1993C......72..847B. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90574-a. PMID 7916655.

- ^ Old LJ (November 1985). "Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)". Science. 230 (4726): 630–632. Bibcode:1985Sci...230..630O. doi:10.1126/science.2413547. PMID 2413547.

- ^ Nedwin GE, Naylor SL, Sakaguchi AY, Smith D, Jarrett-Nedwin J, Pennica D, et al. (September 1985). "Human lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor genes: structure, homology and chromosomal localization". Nucleic Acids Research. 13 (17): 6361–6373. doi:10.1093/nar/13.17.6361. PMC 321958. PMID 2995927.

- ^ Kriegler M, Perez C, DeFay K, Albert I, Lu SD (April 1988). "A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF". Cell. 53 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90486-2. PMID 3349526. S2CID 31789769.

- ^ Tang P, Klostergaard J (June 1996). "Human pro-tumor necrosis factor is a homotrimer". Biochemistry. 35 (25): 8216–8225. doi:10.1021/bi952182t. PMID 8679576.

- ^ Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, et al. (February 1997). "A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells". Nature. 385 (6618): 729–733. Bibcode:1997Natur.385..729B. doi:10.1038/385729a0. PMID 9034190. S2CID 4251053.

- ^ Palladino MA, Bahjat FR, Theodorakis EA, Moldawer LL (September 2003). "Anti-TNF-alpha therapies: the next generation". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 2 (9): 736–746. doi:10.1038/nrd1175. PMID 12951580. S2CID 1028523.

- ^ Olszewski MB, Groot AJ, Dastych J, Knol EF (May 2007). "TNF trafficking to human mast cell granules: mature chain-dependent endocytosis". Journal of Immunology. 178 (9): 5701–5709. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5701. PMID 17442953.

In human cells, contrary to results previously obtained in a rodent model, TNF seems not to be glycosylated and, thus, trafficking is carbohydrate independent. In an effort to localize the amino acid motif responsible for granule targeting, we constructed additional fusion proteins and analyzed their trafficking, concluding that granule-targeting sequences are localized in the mature chain of TNF and that the cytoplasmic tail is expendable for endocytotic sorting of this cytokine, thus excluding direct interactions with intracellular adaptor proteins

- ^ Theiss. A. L. et al. 2005. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha increases collagen accumulation and proliferation in intestinal myofibrobasts via TNF Receptor 2. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. [Online] 2005. Available at: http://www.jbc.org/content/280/43/36099.long Accessed: 21/10/14

- ^ a b c Chadwick W, Magnus T, Martin B, Keselman A, Mattson MP, Maudsley S (October 2008). "Targeting TNF-alpha receptors for neurotherapeutics". Trends in Neurosciences. 31 (10): 504–511. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.005. PMC 2574933. PMID 18774186.

- ^ Wajant H, Pfizenmaier K, Scheurich P (January 2003). "Tumor necrosis factor signaling". Cell Death and Differentiation. 10 (1): 45–65. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401189. PMID 12655295.

- ^ Chen G, Goeddel DV (May 2002). "TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway". Science. 296 (5573): 1634–1635. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1634C. doi:10.1126/science.1071924. PMID 12040173. S2CID 25321662.

- ^ Kant S, Swat W, Zhang S, Zhang ZY, Neel BG, Flavell RA, et al. (October 2011). "TNF-stimulated MAP kinase activation mediated by a Rho family GTPase signaling pathway". Genes & Development. 25 (19): 2069–2078. doi:10.1101/gad.17224711. PMC 3197205. PMID 21979919.

- ^ Gaur U, Aggarwal BB (October 2003). "Regulation of proliferation, survival and apoptosis by members of the TNF superfamily". Biochemical Pharmacology. 66 (8): 1403–1408. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00490-8. PMID 14555214.

- ^ Ghada A. Abd El Latif, Tumor necrosis factor alpha and keratin 17 expression in oral submucous fibrosis in rat model, E.D.J. Vol. 65, (1) Pp 277-288; 2019. doi:10.21608/edj.2015.71414

- ^ Ban L, Zhang J, Wang L, Kuhtreiber W, Burger D, Faustman DL (September 2008). "Selective death of autoreactive T cells in human diabetes by TNF or TNF receptor 2 agonism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (36): 13644–13649. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513644B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803429105. PMC 2533243. PMID 18755894.

- ^ Eastman AJ, Xu J, Bermik J, Potchen N, den Dekker A, Neal LM, et al. (December 2019). "Epigenetic stabilization of DC and DC precursor classical activation by TNFα contributes to protective T cell polarization". Science Advances. 5 (12): eaaw9051. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.9051E. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw9051. PMC 6892624. PMID 31840058.

- ^ Zhao Z, Lan M, Li J, Dong Q, Li X, Liu B, et al. (April 2019). "The proinflammatory cytokine TNFα induces DNA demethylation-dependent and -independent activation of interleukin-32 expression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 294 (17): 6785–6795. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA118.006255. PMC 6497958. PMID 30824537.

- ^ Qi S, Li Y, Dai Z, Xiang M, Wang G, Wang L, et al. (December 2019). "Uhrf1-Mediated Tnf-α Gene Methylation Controls Proinflammatory Macrophages in Experimental Colitis Resembling Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Journal of Immunology. 203 (11): 3045–3053. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1900467. PMID 31611260.

- ^ Song M, Fang F, Dai X, Yu L, Fang M, Xu Y (March 2017). "MKL1 is an epigenetic mediator of TNF-α-induced proinflammatory transcription in macrophages by interacting with ASH2". FEBS Letters. 591 (6): 934–945. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.12601. PMID 28218970.

- ^ Selwood T, Jaffe EK (March 2012). "Dynamic dissociating homo-oligomers and the control of protein function". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 519 (2): 131–143. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.020. PMC 3298769. PMID 22182754.

- ^ Olszewski MB, Groot AJ, Dastych J, Knol EF (May 2007). "TNF trafficking to human mast cell granules: mature chain-dependent endocytosis". Journal of Immunology. 178 (9): 5701–5709. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5701. PMID 17442953.

- ^ Gahring LC, Carlson NG, Kulmar RA, Rogers SW (September 1996). "Neuronal expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha in the murine brain". Neuroimmunomodulation. 3 (5): 289–303. doi:10.1159/000097283. PMID 9218250.

- ^ Walsh LJ, Trinchieri G, Waldorf HA, Whitaker D, Murphy GF (May 1991). "Human dermal mast cells contain and release tumor necrosis factor alpha, which induces endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 88 (10): 4220–4224. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.4220W. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.10.4220. PMC 51630. PMID 1709737.

- ^ Feng P, Jyotaki M, Kim A, Chai J, Simon N, Zhou M, et al. (October 2015). "Regulation of bitter taste responses by tumor necrosis factor". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 49: 32–42. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.001. PMC 4567432. PMID 25911043.

- ^ Said EA, Dupuy FP, Trautmann L, Zhang Y, Shi Y, El-Far M, et al. (April 2010). "Programmed death-1-induced interleukin-10 production by monocytes impairs CD4+ T cell activation during HIV infection". Nature Medicine. 16 (4): 452–459. doi:10.1038/nm.2106. PMC 4229134. PMID 20208540.

- ^ Starkie R, Ostrowski SR, Jauffred S, Febbraio M, Pedersen BK (May 2003). "Exercise and IL-6 infusion inhibit endotoxin-induced TNF-alpha production in humans". FASEB Journal. 17 (8): 884–886. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0670fje. PMID 12626436. S2CID 30200779.

- ^ Pedersen BK (December 2009). "The diseasome of physical inactivity--and the role of myokines in muscle--fat cross talk". The Journal of Physiology. 587 (Pt 23): 5559–5568. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179515. PMC 2805368. PMID 19752112.

- ^ Coppack SW (August 2001). "Pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipose tissue". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 60 (3): 349–356. doi:10.1079/PNS2001110. PMID 11681809.

- ^ Kern L, Mittenbühler MJ, Vesting AJ, Ostermann AL, Wunderlich CM, Wunderlich FT (December 2018). "Obesity-Induced TNFα and IL-6 Signaling: The Missing Link between Obesity and Inflammation-Driven Liver and Colorectal Cancers". Cancers. 11 (1): 24. doi:10.3390/cancers11010024. PMC 6356226. PMID 30591653.

- ^ a b Virdis A, Colucci R, Bernardini N, Blandizzi C, Taddei S, Masi S (February 2019). "Microvascular Endothelial Dysfunction in Human Obesity: Role of TNF-α". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 104 (2): 341–348. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00512. PMID 30165404.

- ^ Hernández-Muñoz I, de la Torre P, Sánchez-Alcázar JA, García I, Santiago E, Muñoz-Yagüe MT, et al. (August 1997). "Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits collagen alpha 1(I) gene expression in rat hepatic stellate cells through a G protein". Gastroenterology. 113 (2): 625–640. doi:10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247485. PMID 9247485.

- ^ Saile B, Matthes N, Knittel T, Ramadori G (July 1999). "Transforming growth factor beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibit both apoptosis and proliferation of activated rat hepatic stellate cells". Hepatology. 30 (1): 196–202. doi:10.1002/hep.510300144. PMID 10385656. S2CID 85343893.

- ^ Pradere JP, Kluwe J, De Minicis S, Jiao JJ, Gwak GY, Dapito DH, et al. (October 2013). "Hepatic macrophages but not dendritic cells contribute to liver fibrosis by promoting the survival of activated hepatic stellate cells in mice". Hepatology. 58 (4): 1461–1473. doi:10.1002/hep.26429. PMC 3848418. PMID 23553591.

- ^ Yang YM, Seki E (December 2015). "TNFα in liver fibrosis". Current Pathobiology Reports. 3 (4): 253–261. doi:10.1007/s40139-015-0093-z. PMC 4693602. PMID 26726307.

- ^ a b Kakino S, Ohki T, Nakayama H, Yuan X, Otabe S, Hashinaga T, et al. (January 2018). "Pivotal Role of TNF-α in the Development and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Murine Model". Hormone and Metabolic Research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et Métabolisme. 50 (1): 80–87. doi:10.1055/s-0043-118666. PMID 28922680. S2CID 25137248.

- ^ Chu PS, Nakamoto N, Ebinuma H, Usui S, Saeki K, Matsumoto A, et al. (July 2013). "C-C motif chemokine receptor 9 positive macrophages activate hepatic stellate cells and promote liver fibrosis in mice". Hepatology. 58 (1): 337–350. doi:10.1002/hep.26351. PMID 23460364.

- ^ Ramadori G, Armbrust T (July 2001). "Cytokines in the liver". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 13 (7): 777–784. doi:10.1097/00042737-200107000-00004. PMID 11474306.

- ^ Dharmalingam M, Yamasandhi PG (2018). "Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 22 (3): 421–428. doi:10.4103/ijem.IJEM_585_17. PMC 6063173. PMID 30090738.

- ^ a b Liang H, Yin B, Zhang H, Zhang S, Zeng Q, Wang J, et al. (June 2008). "Blockade of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor type 1-mediated TNF-alpha signaling protected Wistar rats from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance". Endocrinology. 149 (6): 2943–2951. doi:10.1210/en.2007-0978. PMID 18339717.

- ^ Wandrer F, Liebig S, Marhenke S, Vogel A, John K, Manns MP, et al. (March 2020). "TNF-Receptor-1 inhibition reduces liver steatosis, hepatocellular injury and fibrosis in NAFLD mice". Cell Death & Disease. 11 (3): 212. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2411-6. PMC 7109108. PMID 32235829.

- ^ Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, et al. (June 2006). "MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (6): 1494–1505. doi:10.1172/JCI26498. PMC 1459069. PMID 16691291.

- ^ Murao K, Ohyama T, Imachi H, Ishida T, Cao WM, Namihira H, et al. (September 2000). "TNF-alpha stimulation of MCP-1 expression is mediated by the Akt/PKB signal transduction pathway in vascular endothelial cells". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 276 (2): 791–796. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3497. PMID 11027549.

- ^ Haraoui B, Bykerk V (March 2007). "Etanercept in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 3 (1): 99–105. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.1.99. PMC 1936291. PMID 18360618.

- ^ Salomon BL, Leclerc M, Tosello J, Ronin E, Piaggio E, Cohen JL (2018). "Tumor Necrosis Factor α and Regulatory T Cells in Oncoimmunology". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 444. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00444. PMC 5857565. PMID 29593717.

- ^ Korneev KV, Atretkhany KN, Drutskaya MS, Grivennikov SI, Kuprash DV, Nedospasov SA (January 2017). "TLR-signaling and proinflammatory cytokines as drivers of tumorigenesis". Cytokine. 89: 127–135. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2016.01.021. PMID 26854213.

- ^ Bouwmeester T, Bauch A, Ruffner H, Angrand PO, Bergamini G, Croughton K, et al. (February 2004). "A physical and functional map of the human TNF-alpha/NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (2): 97–105. doi:10.1038/ncb1086. PMID 14743216. S2CID 11683986.

- ^ Micheau O, Tschopp J (July 2003). "Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes". Cell. 114 (2): 181–190. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00521-X. PMID 12887920. S2CID 17145731.

- ^ Clark IA (June–August 2007). "How TNF was recognized as a key mechanism of disease". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 18 (3–4): 335–343. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.04.002. hdl:1885/31135. PMID 17493863. S2CID 36721785.

External links

[edit]- Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P01375 (Tumor necrosis factor) at the PDBe-KB.