List of unusual deaths

Appearance

This list of unusual deaths includes unique or extremely rare circumstances of death recorded throughout history, noted as being unusual by multiple sources.

Antiquity

[edit]| Name of person | Image | Date of death | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

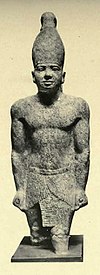

| Menes |  |

c. 3200 BC | According to Manetho, the Egyptian pharaoh and unifier of Upper and Lower Egypt was carried off and then killed by a hippopotamus.[2][3] |

| Teti |  |

c. 2323 BC | According to Manetho, the first king of the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt was mysteriously killed when he was assassinated by one of his own bodyguards. Other sources say he was killed by Userkare, who would then succeed him. His odd death is the earliest-known assassination but is still the subject of speculation.[4][5] |

| Sisera |  |

1200 or 1235 BC | According to Judges 4-5, Sisera, the commander of the Canaanite Army for King Jabin of Hazor, was killed in his sleep when the Kenite woman Jael stabbed him in the temple with a tent peg.[2] |

| Abimelech Ben Gideon |  |

1126 BC | The king of Shechem and son of Gideon was killed in the city of Thebez by a woman who threw a millstone on his head which crushed his skull or mortally wounded him.[6] |

| Tiberinus Silvius |  |

c. 914 BC | It is said that the legendary king of Alba Longa drowned while crossing the Albula river, which became known as the Tiber. This is usually known as the earliest case of someone drowning.[7] |

| Terpander | 7th century BC | The Greek poet and citharode, considered the father of Greek music and lyric poetry, reportedly choked to death on a fig thrown at him during one of his performances.[8] | |

| Draco of Athens |  |

c. 620 BC | The Athenian lawmaker was reportedly smothered to death by gifts of cloaks and hats showered upon him by appreciative citizens at a theatre in Aegina, Greece.[9][10][11] |

| Charondas |  |

c. 612 BC | According to Diodorus Siculus, the Greek lawgiver from Sicily issued a law that anyone who brought weapons into the Assembly must be put to death. One day, he arrived at the Assembly seeking help to defeat some brigands in the countryside, but with a knife still attached to his belt. In order to uphold his own law, he committed suicide.[12][13][14][15] |

| Duke Jing of Jin | 581 BC | In 581 BC a shaman warned the ruler that he would not live to see the new wheat harvest. The ruler dismissed him and had the shaman murdered. However, when the Duke was about to eat the wheat, he felt the need to visit the bathroom. Upon arriving in the bathroom, the Duke fell through the hole and drowned.[11][16] | |

| Arrhichion of Phigalia |  |

564 BC | The Greek pankratiast caused his own death during the Olympic finals. Held by his unidentified opponent in a stranglehold and unable to free himself, Arrhichion kicked his opponent, causing him so much pain from a foot/ankle injury that the opponent made the sign of defeat to the umpires, but at the same time Arrhichion suffered a fatally broken neck. Since the opponent had conceded defeat, Arrhichion was proclaimed the victor posthumously.[17][18] |

| Sisamnes |  |

525 BC | A corrupt Persian judge was killed and flayed alive for accepting a bribe.[19] |

| Milo of Croton |  |

6th century BC | The Olympic champion wrestler's hands reportedly became trapped when he tried to split a tree apart; he was then devoured by wolves (or, in later versions, lions).[20][21][22] |

| Zeuxis |  |

5th century BC | The Greek painter died of laughter while painting an elderly woman.[23][24] |

| Pythagoras of Samos |  |

c. 495 BC | Ancient sources disagree on how the Greek philosopher died,[25][26] but one late and probably apocryphal legend reported by both Diogenes Laërtius, a third-century AD biographer of famous philosophers, and Iamblichus, a Neoplatonist philosopher, states that Pythagoras was murdered by his political enemies. Supposedly, he almost managed to outrun them, but he came to a bean field and refused to run through it, as he had prohibited beans as ritually unclean.[26][27] Since cutting through the field would violate his own teachings, Pythagoras simply stopped running and was killed. This story may have been fabricated by Neanthes of Cyzicus, on whom both Diogenes and Iamblichus rely as a source.[26] |

| Anacreon |  |

c. 485 BC | The poet, known for works in celebration of wine, choked to death on a grape stone according to Pliny the Elder. The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica suggests that "the story has an air of mythical adaptation to the poet's habits".[20][23]: 104 [28][29] |

| Heraclitus of Ephesus |  |

c. 475 BC | According to one account given by Diogenes Laertius, the Greek philosopher was said to have been devoured by dogs after smearing himself with cow manure in an attempt to cure his dropsy.[30][31] |

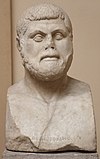

| Themistocles |  |

c. 459 BC | The Athenian general who won the Battle of Salamis actually died of natural causes in exile,[32][33] but was widely rumored to have committed suicide by drinking a solution of crushed minerals known as bull's blood.[32][33][34][35] The legend is widely retold in classical sources. The early twentieth-century English classicist Percy Gardner proposed that the story about him drinking bull's blood may have been based on an ignorant misunderstanding of a statue showing Themistocles in a heroic pose, holding a cup as an offering to the gods. The comedic playwright Aristophanes references Themistocles drinking bull's blood in his comedy The Knights (performed in 424 BC) as the most heroic way for a man to die.[33][36] |

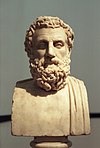

| Aeschylus |  |

c. 455 BC | According to Valerius Maximus, the eldest of the three great Athenian tragedians was killed by a tortoise dropped by an eagle that had mistaken his bald head for a rock suitable for shattering the shell of the reptile. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, adds that Aeschylus had been staying outdoors to avert a prophecy that he would be killed that day "by the fall of a house".[15][20][23]: 104 [37][38][39][40][41][42] |

| Empedocles of Akragas |  |

c. 430 BC | According to Diogenes Laertius, the Pre-Socratic philosopher from Sicily, who, in one of his surviving poems, declared himself to have become a "divine being... no longer mortal",[43] tried to prove he was an immortal god by leaping into Mount Etna, an active volcano.[44][45] The Roman poet Horace also alludes to this legend.[46] |

| Sogdianus | 423 BC | The ruler of the Achaemenid Empire was captured by his half-brother Ochus, who had him executed by being suffocated by ash.[11][47] | |

| Polydamas of Skotoussa |  |

5th century BC | The Thessalian pankratiast, and victor in the 93rd Olympiad (408 BC), was in a cave with friends when the roof began to crumble. Believing his immense strength could prevent the cave-in, he tried to support the roof with his shoulders as the rocks crashed down around him, but was crushed to death.[20][48] |

| Sophocles |  |

c. 406 BC | A number of "remarkable" legends concerning the death of another of the three great Athenian tragedians are recorded in the late antique Life of Sophocles. According to one legend, he choked to death on an unripe grape.[39] Another says that he died of joy after hearing that his last play had been successful.[20][39] A third account reports that he died of suffocation, after reading aloud a lengthy monologue from the end of his play Antigone, without pausing to take a breath for punctuation.[39] |

| Mithridates | 401 BC | The Persian soldier who embarrassed his king, Artaxerxes II, by boasting of killing his rival, Cyrus the Younger (who was the brother of Artaxerxes II), was executed by scaphism. The king's physician, Ctesias, reported that Mithridates survived the insect torture for 17 days.[49][50] | |

| Democritus of Abdera |  |

c. 370 BC | According to Diogenes Laertius, the Greek Atomist philosopher died aged 109; as he was on his deathbed, his sister was greatly worried because she needed to fulfill her religious obligations to the goddess Artemis in the approaching three-day Thesmophoria festival. Democritus told her to place a loaf of warm bread under his nose and was able to survive for the three days of the festival by sniffing it. He died immediately after the festival was over.[51][52] |

| Diogenes of Sinope |  |

c. 323 BC | According to 3rd century biographer, Diogenes Laërtius, he died by consuming raw octopus. His contemporaries, however, claimed he died by holding his breath.[53] |

| Anaxarchus |  |

320 BC | According to Diogenes Laertius, Anaxarchus gained the enmity of the tyrannical ruler of Cyprus, Nicocreon, for an inappropriate joke he made about tyrants at a banquet in 331 BC. When Anaxarchus visited Cyprus, Nicocreon ordered him to be pounded to death in a mortar. During the torture Anaxarchus said to Nicocreon, "Just pound the bag of Anaxarchus, you do not pound Anaxarchus." Nicocreon then threatened to cut his tongue out; Anaxarchus bit it off and spat it at the ruler's face.[54] |

| Antiphanes | c. 310 BC | According to the Suda, the renowned comic poet of the Middle Attic comedy died after being struck by a pear.[55][56] | |

| King Wu of Qin | 307 BC | The king and member of the Qin dynasty reportedly challenged his friend Meng Yue to a lifting contest. When Wu tried to lift a giant bronze pot believed to have been cast for Yu the Great, it crushed his leg, inflicting fatal injuries. Meng Yue and his family were sentenced to death.[11][57] | |

| Susima | 3rd century BC | The crown prince of the Maurya Empire died when he fell into a pit of "hot embers". The trap had been made by Ashoka when he found out his rival was en route.[11] | |

| Agathocles of Syracuse |  |

289 BC | The Greek tyrant of Syracuse was murdered with a poisoned toothpick.[23]: 104 [58] |

| Pyrrhus of Epirus |  |

272 BC | During the Battle of Argos, Pyrrhus was fighting a Macedonian soldier in the street when the elderly mother of the soldier dropped a roof tile onto Pyrrhus' head, breaking his spine and rendering him paralyzed. According to a soldier named Zopyrus, they then proceeded to decapitate the king.[59] |

| Philitas of Cos |  |

c. 270 BC | The Greek intellectual is said by Athenaeus to have studied arguments and erroneous word usage so intensely that he wasted away and starved to death.[60] British classicist Alan Cameron speculates that Philitas died from a wasting disease which his contemporaries joked was caused by his pedantry.[61] |

| Zeno of Citium |  |

c. 262 BC | The Greek philosopher from Citium (Kition), Cyprus, tripped and fell as he was leaving the school, breaking his toe. Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe, "I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?" He died on the spot through holding his breath.[62] |

| Qin Shi Huang |  |

August 210 BC | The first emperor of China, whose artifacts and treasures include the Terracotta Army, died after ingesting several pills of mercury, in the belief that it would grant him immortality.[15][63][64][65] |

| Chrysippus of Soli |  |

c. 206 BC | One ancient account of the death of the third-century BC Greek Stoic philosopher tells that he died laughing at his own joke[66] after he saw a donkey eating his figs; he told a slave to give the donkey neat wine to drink with which to wash them down, and then, "...having laughed too much, he died" (Diogenes Laërtius 7.185).[15][40][41][67][note 1] |

| Eleazar Avaran |  |

c. 163 BC | The brother of Judas Maccabeus; according to 1 Maccabees 6:46, during the Battle of Beth Zechariah, Eleazar spied an armored war elephant which he believed to be carrying the Seleucid emperor Antiochus V Eupator. After thrusting his spear in battle into its belly, it collapsed and fell on top of Eleazar, killing him instantly.[40][68] |

| Manius Aquillius and Marcus Licinius Crassus |   |

1st century BC | The late Roman Republic-era consul was sent as ambassador to Asia Minor in 90 BC to restore Nicomedes IV of Bithynia to his kingdom after the latter was expelled by Mithridates VI of Pontus. But Aquillius encouraged Nicomedes to raid part of Mithridates' territory, which started the First Mithridatic War. Aquillius was captured and brought to Mithridates, who in 88 BC had him executed by pouring molten gold down his throat. According to one story, Marcus Licinius Crassus, a Roman general and statesman, who was very greedy despite being called "the richest man in Rome," was executed in the same manner by the Parthians after they defeated him in the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, in symbolic mockery of his thirst for wealth. However, it has been disputed as to whether this is how Crassus met his end.[69][70] |

| Quintus Lutatius Catulus | 87 BC | After his former comrade-in-arms Gaius Marius took control of Rome and had him prosecuted for a capital offence, the Roman Republic consul shut himself inside his house, which was heated to a high temperature and daubed with lime, thus suffocating himself.[20][71] | |

| Licinius Macer | 66 BC | At the end of his trial by Cicero for extortion, the Roman annalist and politician suffocated himself with a handkerchief, thus nullifying his conviction.[20] | |

| Porcia Catonis |  |

June 43 BC to October 42 BC | The daughter of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis and second wife of Marcus Junius Brutus, according to ancient historians such as Cassius Dio and Appian, killed herself by swallowing hot coals.[72] Modern historians find this tale implausible.[73] |

| Cleopatra and two handmaidens |  |

August 30 BC | The 39-year-old last queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom killed herself with an asp (a viper). Two of her handmaidens were also bitten by the asp.[11] |

| Tiberius Claudius Drusus |  |

c. 20 AD | According to Suetonius, the eldest son of the future Roman emperor Claudius died while playing with a pear. Having tossed the pear high in the air, he caught it in his mouth when it came back, but he choked on it, dying of asphyxia.[74][75] |

| Tiberius |  |

16 March 37 | The Roman emperor died in Misenum aged 78. According to Tacitus, the emperor appeared to have died and Caligula, who was at Tiberius' villa, was being congratulated on his succession to the empire, when news arrived that the emperor had revived and was recovering his faculties. Those who had moments before recognized Caligula as Augustus fled in fear of the emperor's wrath, while Macro, a prefect of the Praetorian Guard, took advantage of the chaos to have Tiberius smothered with his own bedclothes, definitively killing him.[76] |

| Saint Peter |  |

Between 64 and 68 AD | The apostle of Jesus was crucified upside-down in Rome, based on his claim of being unworthy to die in the same way as his Saviour.[77][78] |

| Bartholomew the Apostle |  |

69 or 71 AD | St. Bartholomew, an apostle of Jesus Christ, died after either being knocked out and thrown into the sea or being skinned alive and beheaded in Armenia.[79] |

| Antipas of Pergamum |  |

68 or 92 AD | Antipas was burned alive inside the brazen bull for supposedly casting out demons who were worshipped in Pergamum.[80] |

| Simon the Zealot |  |

1st century AD | According to an ancient tradition, the apostle of Jesus was sawn in half in Persia.[81] |

| Saint Lawrence |  |

258 | The deacon was roasted alive on a giant grill during the persecution of Valerian.[82][83] Prudentius tells that he joked with his tormentors, "Turn me over—I'm done on this side".[84] He is now the patron saint of cooks, chefs, and comedians.[85] |

| Marcus of Arethusa |  |

362 | The Christian bishop and martyr was hung up in a honey-smeared basket for bees to sting him to death.[23]: 104 |

| Cassian of Imola | 13 August 363 | Cassian of Imola was sentenced to death by Julian the Apostate and was handed over to his pupils to carry out the deed, which they did by binding him to a stake and stabbing him with a poisoned stylus.[86] | |

| Valentinian I |  |

17 November 375 | The Roman emperor suffered a stroke which was provoked by yelling at foreign envoys in anger.[11][87] |

| Attila |  |

c. 453 | Attila the Hun reportedly died on his wedding night by choking on his own blood, which flowed into his mouth from a nosebleed.[41][88][89] |

Middle Ages

[edit]| Name of person | Image | Date of death | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constans II |  |

15 July 668 | The Byzantine Emperor was assassinated with a bucket according to Theophilus of Edessa.[90] |

| Li Bai |  |

30 November 762 | The famous Chinese poet of the 8th century died drunk after embracing the Moon. While riding his boat along the Yangtze River, he saw the reflection of the Moon in the water. When he tried to hug it, he fell off his boat and later drowned.[91] |

| Popiel |  |

830 | According to legend, after the wife of the dissolute Polish ruler poisoned his uncles to prevent them from deposing him, a horde of rats and mice swarmed out of the uncles' bodies, which had been cast into lake Gopło, pursued Popiel and his wife to a tower in which they had taken refuge and ate them alive.[92] |

| Ragnar Lodbrok |  |

c. 865 | The semi-legendary Viking leader whose exploits are narrated in the Ragnars saga loðbrókar, a thirteenth-century Icelandic saga, is said to have been captured by Ælla of Northumbria, who had him executed by throwing him into a pit of snakes.[15][93] |

| Louis III of France |  |

5 August 882 | The king of West Francia died aged around 18 at Saint-Denis. Whilst mounting his horse to pursue a girl who was running to seek refuge in her father's house, he hit his head on the lintel of a low door and fell, fracturing his skull.[94] |

| Basil I |  |

29 August 886 | The Byzantine emperor's belt was entangled between antlers of a deer during a hunt and the animal subsequently dragged him for 16 miles (26 km) through the woods. Because of this accident, Basil contracted fever and he died shortly afterwards.[95][96] |

| Sigurd the Mighty of Orkney |

|

892 | The second Earl of Orkney strapped the head of his defeated foe Máel Brigte to his horse's saddle. Brigte's teeth rubbed against Sigurd's leg as he rode, causing a fatal infection, according to the Old Norse Heimskringla and Orkneyinga sagas.[15][89][96][97] |

| Hatto II |  |

18 January 970 | The archbishop of Mainz, like the Polish ruler Popiel, is claimed in legend to have been eaten alive by rodents.[98] |

| Abu Nasr al-Jawhari |  |

1003 or 1010 | The Kazakh Turkic scholar from Farab died after a failed aviation test. It is said he used two wooden wings and rope. He leaped off the roof of the Nisābūr Mosque and then died on impact. His death was most likely caused after he had delusions of being a bird. al-Jawhari is said to be the first person killed by an aviation invention.[99] |

| Edmund Ironside |  |

30 November 1016 | The English king was allegedly stabbed whilst on a toilet by an assassin hiding underneath.[100][101] |

| Béla I of Hungary |  |

11 September 1063 | After the Holy Roman Empire decided to launch a military expedition against Hungary to restore young Solomon to the throne, the Hungarian king was seriously injured when "his throne broke beneath him" in his manor at Dömös.[15][102] The king—who was "half-dead", according to the Illuminated Chronicle—was taken to the western borders of his kingdom, where he died at the creek Kanizsa on 11 September 1063.[15][103][104] |

| Victims of the White Ship wreck |  |

25 November 1120 | While carrying intoxicated nobles across the English Channel, the ship was crashed into a rock by the also-intoxicated helmsman and began sinking. A lifeboat was launched, but William Adelin jumped into and capsized it. All aboard died.[15] |

| Crown Prince Philip of France |

|

13 October 1131 | Died while riding through Paris when his horse tripped over a black pig that was running out of a dung heap.[15][96][105][106] |

| Henry I of England |  |

1 December 1135 | While visiting relatives, he supposedly ate too many lampreys against his physician's advice, causing a pain in his gut, and ultimately his death.[15][41][101][107] |

| John II Komnenos |  |

1 April 1143 | Cut himself with a poisoned arrow during a boar hunt, and subsequently died from an infection.[108] |

| Pope Adrian IV |  |

1 September 1159 | The only Englishman to serve as Pope reportedly died after choking on a fly while drinking spring water.[89][96][109][110][111] |

| Victims of the Erfurt latrine disaster |  |

26 July 1184 | While Henry VI, the King of Germany, was holding an informal assembly at the Petersburg Citadel in Erfurt, the combined weight of the assembled nobles caused the wooden second story floor of the building to collapse. Most of the nobles fell through into the latrine cesspit below the ground floor, where about 60 of them drowned in liquid excrement.[96][112] |

| Frederick Barbarossa |  |

10 June 1190 | While leading the German army on the Third Crusade, the Holy Roman Emperor unexpectedly drowned while bathing in the Saleph River.[113][114] |

| Henry I of Castile |  |

6 June 1217 | The 13-year-old king of Castile was killed by a tile that fell from a roof.[115][116] |

| Gruffudd ap Llywelyn ap Iorwerth |  |

1 March 1244 | The first-born son of Llywelyn the Great died while attempting to lower himself from the Tower of London in an escape attempt. The rope, made out of sheets and other fabrics, snapped, and his neck was broken in the fall, according to English monk and chronicler, Matthew Paris.[96] |

| Al-Musta'sim |  |

20 February 1258 | The last Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad, was executed by his Mongol captors by being rolled up in a rug and then trampled by horses.[15][117] |

| Edward II of England |  |

21 September 1327 | The English king was rumoured to have been murdered after being deposed and imprisoned by his wife Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer, by having a horn pushed into his anus through which a red-hot iron was inserted, burning out his internal organs without marking his body.[89][101][118][119][120] However, there is no real academic consensus on the manner of Edward II's death, and it has been plausibly argued that the story is propaganda.[120][121] |

| John of Bohemia |  |

26 August 1346 | After being blind for 10 years, the Bohemian king died in the Battle of Crécy when—at his command—his companions tied their horses' reins to his own and charged. He was slaughtered in the ensuing fight.[15][122][123] |

| Charles II of Navarre |  |

1 January 1387 | The contemporary chronicler Froissart relates that the king of Navarre, known as "Charles the Bad", suffering from illness in old age, was ordered by his physician to be tightly sewn into a linen sheet soaked in distilled spirits. The highly flammable sheet accidentally caught fire, and Charles later died of his injuries. Froissart considered the horrific death to be God's judgment upon the king.[124][125][126] |

| Martin of Aragon |  |

31 May 1410 | The Aragonese king died from a combination of indigestion and uncontrollable laughing. According to legend, Martin was suffering from indigestion, caused by eating an entire goose, when his favorite jester, Borra, entered the king's bedroom. When Martin asked Borra where he had been, the jester replied with: "Out of the next vineyard, where I saw a young deer hanging by his tail from a tree, as if someone had so punished him for stealing figs." This joke caused the king to die from laughter.[89][96][127][128] |

Renaissance

[edit]| Name of person | Image | Date of death | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence |  |

18 February 1478 | The 1st Duke of Clarence was allegedly executed by drowning in a barrel of Malmsey wine, apparently his own choice once he accepted he was to be killed.[15][96][129] |

| Charles VIII of France |  |

7 April 1498 | The French king died as the result of striking his head on the lintel of a door while on his way to watch a game of real tennis.[23]: 105 |

| Victims of the 1518 dancing plague |  |

July 1518 | Several people died of either heart attacks, strokes or exhaustion during a dancing mania that occurred in Strasbourg, Alsace (Holy Roman Empire).[15][130][131] |

| Robert Pakington | 13 November 1536 | The 47-year-old merchant was killed in London by a wheellock pistol, making his death the first political assassination performed by a firearm.[132] | |

| Pietro Aretino |  |

21 October 1556 | The influential Italian author and libertine is said to have died of suffocation from laughing too much at an obscene joke during a meal in Venice. Another version states that he fell from a chair from too much laughter, fracturing his skull.[42][133] |

| Henry II of France |  |

10 July 1559 | On 30 June 1559, a tournament was held near Place des Vosges to celebrate the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis with the French king's longtime enemies, the Habsburgs of Austria, and to celebrate the marriage of his daughter Elisabeth of Valois to King Philip II of Spain. During a jousting match, Henry, wearing the colors of his mistress Diane de Poitiers,[134] was wounded in the eye by a fragment of the splintered lance of Gabriel Montgomery, captain of the King's Scottish Guard.[135] Despite the efforts of royal surgeons Ambroise Paré and Andreas Vesalius, the court doctors ultimately "advocated a wait-and-see strategy";[136] as a result, the king's untreated eye and brain damage led to his death by sepsis ten days later.[137] His death played a significant role in the decline of jousting as a sport, particularly in France.[138] |

| Amy Robsart |  |

8 September 1560 | The 28-year-old wife of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was found dead by a staircase with two wounds on her head and a broken neck. Theories suggest she threw herself down the stairs.[139][140] |

| Hans Staininger |  |

1567 | The burgomaster of Braunau (then Bavaria, now Austria), died when he broke his neck by tripping over his own beard.[141] The beard, which was 4.5 feet (1.4 m) long at the time, was usually kept rolled up in a leather pouch.[142] |

| Marco Antonio Bragadin |  |

17 August 1571 | The Venetian Captain-General of Famagusta in Cyprus, was gruesomely killed after the Ottomans took over the city. He was dragged around the walls with sacks of earth and stone on his back; next, he was tied to a chair and hoisted to the yardarm of the Turkish flagship, where he was exposed to the taunts of the sailors. Finally, he was taken to his place of execution in the main square, tied naked to a column, and flayed alive.[143] Bragadin's skin was stuffed with straw and sewn, reinvested with his military insignia, and exhibited riding an ox in a mocking procession along the streets of Famagusta. The macabre trophy was hoisted upon the masthead pennant of the personal galley of the Ottoman commander, Amir al-bahr Mustafa Pasha, to be taken to Constantinople as a gift for Sultan Selim II. Bragadin's skin was stolen in 1580 by a Venetian seaman and brought back to Venice, where it was received as a returning hero.[144] |

| Victims of the Black Assize of Oxford 1577 |  |

July 1577 | In Oxford, England, at least 300 people, including Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer Sir Robert Bell and Serjeant Nicholas Barham, died in the aftermath of the trial of Rowland Jenkes, a Catholic bookseller convicted of distributing pamphlets defaming Queen Elizabeth I, at the assize at Oxford. The dead reportedly included no women or children.[145] |

| Mary, Queen of Scots |  |

8 February 1587 | The 44-year-old queen of Scotland was told that she was to be executed for plotting the assassination of her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I. However, when the executioner, only known as Bull, prepared to chop off her head with an axe, the first blow did not kill Mary. It only hit her head. The second blow severed her neck, but the tendon was still left. The executioner later pulled off Mary's head only to reveal that her hair was a wig.[89][146] |

| Andrew Perne |  |

26 April 1589 | The Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University and Dean of Ely was known for his frequent religious conversions to match the established faith of the time in England. He reportedly died due to having heard the jester of Queen Elizabeth I make a joke about his uncertain spiritual state, referring to him as "one that is neither heaven nor earth, but hangs betwixt both".[147] |

| Tycho Brahe |  |

24 October 1601 | The astronomer contracted a bladder or kidney ailment after attending a banquet in Prague and died eleven days later. According to Johannes Kepler's first-hand account, Brahe had refused to leave the banquet to relieve himself, because it would have been a breach of etiquette.[41][148][149] After he had returned home, he was no longer able to urinate, except eventually in very small quantities and with excruciating pain.[41][150] Though initially ascribed to a kidney stone, and later still to potential mercury poisoning, modern analyses indicate Brahe's death resulted from a fatal case of uremia caused by an inflamed prostate.[151][152] |

Early modern period

[edit]| Name of person | Image | Date of death | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Francis Bacon |  |

9 April 1626 | The English philosopher and statesman died of pneumonia after stuffing a chicken carcass with snow to learn whether it could preserve meat.[41][42] |

| Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke |  |

30 September 1628 | A disgruntled servant stabbed the English poet, dramatist and statesman in the stomach after he used the toilet. Physicians treated the wounds with animal fat, which rotted, causing a fatal case of gangrene.[42] |

| Jörg Jenatsch |  |

24 January 1639 | The Swiss political leader was assassinated by a person who dressed in a bear costume so he could assassinate him with an axe. Other stories say that the axe was the same one that Jenatsch had used to kill a rival.[120] |

| Safi of Persia |  |

12 May 1642 | The Safavid ruler of Iran allegedly died due to alcohol intoxication in a drinking contest against a Georgian nobleman, Scedan Chiladze, invited from Mingrelia.[153] |

| Thomas Granger |  |

8 September 1642 | Granger was executed for buggery with a mare, a cow, two goats, five sheep, two calves, and a turkey. Granger was one of the first people to be executed in the Plymouth Colony and the first Caucasian juvenile to be sentenced to death and executed in the territory of what is now the United States. The mare, the cow and the calves were also executed.[154] |

| Arthur Aston |  |

1649 | During the Siege of Drogheda, Arthur Aston was beaten to death by Oliver Cromwell's army with his own wooden leg because they suspected gold coins were concealed inside.[155] |

| Thomas Urquhart |  |

1660 | The Scottish aristocrat, polymath, and first translator of François Rabelais's writings into English is said to have died laughing upon hearing that Charles II had taken the throne.[42][156][157] |

| James Betts | 1667 | Died from asphyxiation after being sealed in a cupboard by Elizabeth Spencer, at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, in an attempt to hide him from her father, John Spencer.[158][159] | |

| François Vatel |  |

24 April 1671 | The majordomo of Prince Louis II de Bourbon-Condè was responsible for a banquet for 2,000 people hosted in honour of King Louis XIV at the Château de Chantilly, where he died. According to a letter by Madame de Sévigné, Vatel was so distraught about the lateness of the seafood delivery and about other mishaps, that he committed suicide with his sword, and his body was discovered when someone came to tell him of the arrival of the fish.[40][160] |

| Molière |  |

17 February 1673[42][161] | The French playwright suffered a pulmonary hemorrhage caused by tuberculosis while playing the part of a hypochondriac in his own play Le malade imaginaire.[42][161][162] He disguised his convulsion as part of his performance and finished out the show,[161] which ends with his character dead in a chair. After the show, he was carried in the chair to his house, where he died.[161][162][163] |

| Thomas Otway |  |

14 April 1685 | The English dramatist fell on hard times and was suffering from poverty in his later years, and was driven by starvation to beg for food. A gentleman who recognized him gave him a guinea, with which he hastened to a baker's shop, purchased a roll, and choked to death on the first mouthful.[164] |

| Jean-Baptiste Lully |  |

22 March 1687 | The French composer died of a gangrenous abscess after accidentally piercing his foot with a staff while he was vigorously conducting a Te Deum. It was customary at that time to conduct by banging a staff on the floor. He refused to have his leg amputated so he could still dance.[165] |

| William III of England |  |

8 March 1702 | The king of England was riding his horse when it stumbled on a molehill. William fell and broke his collarbone, then contracted pneumonia and died several days later. After he died, Jacobites were said to have toasted in the mole's honour, calling it "the little gentleman in the black velvet waistcoat".[101] |

| Hannah Twynnoy |  |

October 1703 | The 33-year-old barmaid of The White Lion was mauled to death by a tiger in Malmesbury, Wiltshire. She was the first person to be killed by a tiger in British history.[166] |

| Edward Teach |  |

22 November 1718 | The famous English pirate was shot five times and slashed ~20 times with swords by Robert Maynard and his men. He was still alive, but died a day later on the 22nd.[89] |

| Sarah Grosvenor | 14 September 1742 | The 19-year-old woman was getting an abortion from Dr. John Hallowell. However, on the 14th, she died from the complications of the surgery. Grosvenor was the first case of a surgical abortion.[167] | |

| Frederick, Prince of Wales |  |

31 March 1751 | The son of George II of Great Britain and father of George III died of a pulmonary embolism, but was commonly claimed to have been killed by being struck by a cricket ball.[23]: 105 [168] |

| Professor Georg Wilhelm Richmann |  |

6 August 1753 | The Russian physicist was killed when a globe of ball lightning which he created in his laboratory struck him in the forehead.[169][170] |

| Henry Hall | 8 December 1755 | The 94-year-old British lighthouse keeper died several days after fighting a fire at Rudyerd's Tower, during which molten lead from the roof fell down his throat. His autopsy revealed that "the diaphragmatic upper mouth of the stomach greatly inflamed and ulcerated, and the tuncia in the lower part of the stomach burnt; and from the great cavity of it took out a great piece of lead ... which weighed exactly seven ounces, five drachms and eighteen grains". The piece of lead is currently in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland.[171][172] | |

| John Day | 22 June 1774 | The English carpenter and wheelwright was the first human known to have died in an accident with a submarine. Day submerged himself in Plymouth Sound in a wooden diving chamber attached to a sloop named the Maria and never resurfaced.[173] | |

| Unknown concubine of King Tetui of Mangaia | 1777 | In approximately 1777, a concubine of King Tetui was killed by a falling coconut on the island Mangaia in the Cook Islands.[174] | |

| Col. Francis Barber |  |

2 February 1783 | The 32-year-old colonel was killed when a tree fell on top of him as he was riding his horse to dine with George Washington[175] in Newburgh, New York.[176] |

| James Otis Jr. |  |

23 May 1783 | The 58-year-old son of famed lawyer James Otis was killed by a lightning strike in Andover, Massachusetts.[177][178] |

| Frantisek Kotzwara |  |

2 September 1791 | While in London, the 31-year-old Czech violinist visited a prostitute named Susannah Hill and requested his neck be tied with a noose around a door knob. He died after the sexual intercourse of erotic asphyxiation.[179] |

| Samuel Spencer | 20 March 1793 | A former colonel from North Carolina was sleeping on a porch in Anson County while wearing a red cap. Spencer's bobbling head drew the attention of a turkey, which viewed Spencer as another turkey and fatally wounded the 59-year-old with its talons.[180][181] |

19th century

[edit]| Name of person | Image | Date of death | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Millwood |  |

3 January 1804 | The 32-year-old plasterer was shot and killed by excise officer Francis Smith, who mistook him for the Hammersmith ghost due to his white uniform. Smith was later sentenced to death, but his sentence was commuted to one year's imprisonment with hard labor, and he received a full pardon later in the year.[40][182] |

| Victims of the London Beer Flood |  |

17 October 1814 | At Meux & Co's Horse Shoe Brewery, a 22-foot-tall (6.7 m) wooden vat of fermenting porter burst, causing chain reactions and destroying several large beer barrels. The beer subsequently flooded the nearby slum and killed eight people. Several people also subsequently died from alcohol poisoning as a result of vaporized liquor.[183][184][185] |

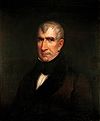

| William Henry Harrison |  |

4 April 1841 | The 9th President of the United States died a month after his inauguration from an illness (possibly pneumonia or enteric fever) that developed after he stood in the rain to deliver his 2-hour-long inaugural address, the longest by any U.S. President. Medical treatments Harrison received in the last week of his life included opium, castor oil and leeches. Harrison remains the U.S. President to have served the shortest term in office and was the first President to die in office.[41][186] |

| Zachary Taylor |  |

9 July 1850 | The 12th President of the United States died of diarrhea and dysentry 5 days after consuming raw cherries and iced milk at a 4th of July event at the site of the Washington Monument.[41][187][188] Persistent speculation that Taylor was poisoned would lead to the exhumation of some of his remains in 1991, but scientific testing found no evidence of poison.[187][188] |

| William Snyder | 11 January 1854 | The 13-year-old died in San Francisco, California, reportedly after a circus clown named Manuel Rays swung him around by his heels.[189][190] | |

| Victims of the 1858 Bradford sweets poisoning |  |

1858 | In Bradford, England, a batch of sweets accidentally poisoned with arsenic trioxide were sold by William Hardaker, colloquially referred to as "Humbug Billy". Around five boxes of sweets were delivered and sold. Around 20 people died and 200 people suffered from the effects of the poison.[191][192] |

| Julius Peter Garesché |  |

31 December 1862 | The Cuban-born professional soldier was killed on the first day of the Battle of Stones River when a cannon ball decapitated him.[193][194] |

| Archduchess Mathilda of Austria |  |

6 June 1867 | The daughter of Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen set her dress on fire while trying to hide a cigarette from her father, who had forbidden her to smoke.[195][196] |

| Mary Ward |  |

31 August 1869 | The 42-year-old Irish scientist, naturalist, microscopist, author, and artist was killed by a steam-powered car built by William Parsons' sons. While Ward was riding in the car, it hit a bend, causing Ward to fall out of the car. One of the car's wheels ran over her and broke her neck. She is the first person known to have been killed by a motor vehicle.[197][198] |

| Clement Vallandigham |  |

17 June 1871 | The American politician and lawyer, who was defending a man accused of murder, accidentally shot himself while demonstrating how the victim might have done so. His client was acquitted.[15][199][200] |

| James "Jim" Cullen | 6 November 1873 | The 25-year-old Irish man became the only man ever lynched in Mapleton, Maine,[201] after he committed a robbery and beat two deputy sheriffs to death with an axe.[202][203][204] | |

| Unknown man | 1875 | A factory worker in Manchester found a mouse on her table and screamed. A man rushed over to her and tried to shoo it away, but it tried to hide in his clothes, and when he gasped in surprise the mouse dove into his mouth and he swallowed it. The mouse tore and bit the man's throat and chest, and he later died "in horrible agony".[205][206] | |

| Victims of the Dublin Whiskey Fire |  |

18 June 1875 | At The Liberties, Dublin, Ireland (then part of the United Kingdom), a fire broke out at Laurence Malone's bonded storehouse on the corner of Ardee Street, where 5,000 hogsheads (262,500 imperial gallons or 1,193,000 litres or 315,200 US gallons) of whiskey were being stored. The heat caused the barrels in the storehouse to explode, sending a stream of whiskey flowing through the doors and windows of the burning building. The burning whiskey then flowed along the streets where it quickly demolished a row of small houses. Despite the damage from the fire, all of the resulting 13 fatalities were caused by alcohol poisoning after drinking the undiluted flooded whiskey.[207][208] |

| Queen Sunanda Kumariratana |  |

31 May 1880 | The 19-year-old queen consort of King Rama V of Siam died when her boat flipped over. A large crowd formed but none of them could help because touching the queen was a capital offense.[41][209] |

| Hague and another female servant | October 1881 | A British servant of one Mr. Birchall was instructed by his master to retrieve a four-chambered pistol.[210] Hague did so, but while examining the gun he shot himself in the jaw which caused instant death. He was discovered by another servant who also shot herself.[211] | |

| Sir William Payne-Gallwey, 2nd Baronet | 19 December 1881 | The former British MP died after sustaining severe internal injuries when he fell on a turnip while hunting.[212][213] | |

| Samuel Wardell | 31 December 1885 | The lamplighter in Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York, had attached a 10-pound (4.5 kg) rock to his alarm clock, which would crash to the floor and awaken him. On Christmas Eve, he rearranged his furniture for a party, but forgot to change his room back afterwards. When the alarm mechanism went off the next morning, the rock fell on his head and killed him.[205][214][215] | |

| George Murichson | 13 May 1886 | The 8-year-old boy from Aroostook County, Maine, died from a hemorrhage after having a live snake pulled out of his mouth. The snake was speculated to have gone down his throat after he had "gone to sleep in some field".[216][217][218] | |

| Mary Agnes Lapish | April 1893 | The Australian woman stumbled into a barbed-wire fence, possibly while intoxicated, and was strangled by her fur collar.[219][220] | |

| Jeremiah Haralson |  |

1895 | The former United States Congressman from Alabama disappears from the historical record after his 1895 imprisonment for pension fraud in Albany, New York. He was reportedly killed by an unknown animal while coal mining near Denver, Colorado, c. 1916, but there is little or no historical evidence for this.[221][222] |

| Bridget Driscoll |  |

17 August 1896 | The 44-year-old, the first recorded case of a pedestrian killed in a collision with a motor car in Great Britain,[223] was struck on the grounds of the Crystal Palace in London, by a car belonging to the Anglo-French Motor Carriage Company while giving demonstration rides.[224] |

| Empress Elisabeth of Austria |  |

10 September 1898 | Stabbed with a thin file by Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni while strolling through Geneva with her lady-in-waiting Irma Sztáray. The wound pierced her pericardium and a lung. Her extremely tight corset held the wound closed, so she did not realize what had happened (believing a passerby had struck her), and walked on for some time before collapsing.[225][226] |

20th century

[edit]1900–1960

[edit]| Name of person | Image | Date of death | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victims of the 1900 English beer poisoning |  |

1900 | In the English Midlands, North West England, and Manchester, doctors saw that avid drinkers had numbness in the hands or feet. However, around 41 people succumbed to peripheral neuritis, and people decided to investigate. They discovered the cause to be alcoholic neuropathy caused by non-purified sulphuric acid laced with arsenic. Over 6,000 people died from the poison and most of the victims were paralyzed from the effects.[227][228] |

| Jesse William Lazear |  |

25 September 1900 | The 34-year-old American physician was convinced that mosquitoes were carriers for yellow fever. He allowed himself to be bitten by multiple mosquitoes and died days later from the disease.[19][229] |

| Victims of the Thanksgiving Day Disaster |  |

29 November 1900 | During the 1900 The Big Game American football match between the California Golden Bears and the Stanford Cardinal in San Francisco, a large crowd of people who did not want to pay the $1 (equivalent to $37 in 2023) admission fee gathered upon the roof of a glass blowing factory to watch for free. The roof collapsed, spilling many spectators onto a furnace. Of the hundreds of people on the roof, at least 100 people fell four stories to the factory floor. 60 to 100 more people fell directly on top of the furnace, the surface temperature of which was estimated to be around 500 °F (260 °C). Fuel pipes were severed as a result of the roof collapse, spraying many victims with scalding hot oil. The fuel also ignited, setting many bodies on fire.[230] Twenty-three people were killed, and over 100 more were injured. The disaster remains the deadliest accident at a sporting event in U.S. history.[231] |

| James Doyle Jr. | 30 January 1901 | The lineworker in Smartsville, California, was killed by an electric shock through a telephone receiver after a broken power line came in contact with the telephone wire.[232] | |

| Adelbert S. Hay |  |

23 June 1901 | The 24-year-old American consul and politician died after falling 60 feet (18 m) from a window in the New Haven House in New Haven, Connecticut. The San Francisco Call speculated that Hay had been sitting on the window for air and eventually fell asleep, causing him to fall to his death.[233] |

| Mary Franks | 12 July 1902 | The woman died from suffocation caused by "matter from her tongue" which went into her throat after a tooth extraction.[234] | |

| Jessie Smith | August 1902 | The elderly woman in Te Aroha was found dead behind her house in a tank. She had come out of an asylum before her disappearance.[235] | |

| R. Stanton Walker | 25 October 1902 | The 20-year-old was watching an amateur baseball game in Morristown, Ohio, with a friend on either side of him. One of the friends borrowed a knife from the other to sharpen his pencil as he was keeping score, and when he was finished passed the knife to Walker to pass to the other friend. As Walker was holding the knife, a foul ball struck him in the hand and drove the knife into his chest next to his heart. His friends asked if he was hurt and he said "not much", but the wound soon began to bleed heavily and he died within minutes.[236][237] | |

| Unknown Hawaiian male | May 1903 | An unidentified person was beaten to death with a Bible during a healing ceremony gone wrong in Honolulu, Hawai'i.[238][failed verification] He was being treated for malaria when his family summoned a Kahuna, who decided he was possessed by devils and tried to exorcise the demons;[239][failed verification] the Kahuna was charged with manslaughter.[citation needed] | |

| Romaine Romania and John Banks | 26 May 1903 | Romania, a 45-year-old native of Belgium, died in Norfolk, Virginia, after taking a large amount of calomel, eating several oranges, and drinking a considerable amount of beer. Romania's head swelled to twice normal size. That same day, barge worker John Banks was electrocuted when the rigging of his vessel came in contact with the wires crossing a bridge belonging to the Norfolk Railway and Light Company.[240] | |

| Ed Delahanty |  |

2 July 1903 | The American baseball player for the Phillies died after being removed from a train while drunk, falling off International Bridge, and going over Niagara Falls. Delahanty reportedly downed five shots of whiskey, broke into a fire axe case, attempted to shove over a partition, and allegedly grabbed a woman's ankles and tried to pull her out of her berth. He may also have threatened other passengers with razor blades. The conductor removed him from the train and asked him to calm down because he was still in Canada, to which he allegedly shouted, "I don't care if I'm in Canada or dead!" He later encountered and may have scuffled with Sam Kingston, a local night watchman, after which he went into the river and over the Falls. Kingston's account of the incident was spotty and inconsistent; it is unclear whether Delahanty was intentionally pushed, accidentally fell, or decided to jump.[241] |

| Benjamin Taylor A Bell | 1 March 1904 | On 18 February 1904, while taking his habitual shortcut to the Canadian Mining Review offices through an adjacent store, the Canadian journalist walked through the wrong door in the store and fell 10 feet (3.0 m) down an elevator shaft. He died of his injuries 12 days later.[242] | |

| John Mortensen | 1 May 1904 | The 19-year-old duck hunter from Wairoa, New Zealand, drowned in about 6 inches (15 cm) of water on the Whare-o-Maraenui reserve in Napier, New Zealand, apparently having fallen while having a seizure.[243] | |

| Benjamin and Edwin Coshkey | 24 June 1904 | Two brothers picking cherries near Wabank, Lancaster Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, were electrocuted when they made contact with an exposed wire in the branches.[244] | |

| John Ericsen | 4 July 1904 | The 11-year-old boy from Butte, Montana, went missing on 4 July and was found dead 4 days later under a pile of coal in a bin near the North Pacific roundhouse.[245] | |

| Melissa M. Tiemann | 7 July 1904 | The 50-year-old resident of Los Angeles fell from a streetcar and struck the back of her head on the ground, driving the teeth of an aluminum comb she was wearing into her skull.[246] | |

| Clarence Madison Dally |  |

2 October 1904 | The 39-year-old American glassblower died from radiation on his hands while using a handmade X-ray. Dally is the first person known to have died from X-ray exposure.[247] |

| Jane Stanford |  |

28 February 1905 | The founder of Stanford University died mysteriously from strychnine poisoning. The case of her death was rumored as poisoning, but later changed into "natural causes," according to David Starr Jordan. Who or what killed Stanford is still a mystery.[248] |

| Charles Persich | March 1905 | The baby from Sydney died from intussusception, meaning that his bowels had "telescoped".[249] | |

| Thomas Melia | 9 December 1905 | An employee of a brewery in Brooklyn died when he was caught in "an avalanche of shifting malt and barley and was suffocated."[250] | |

| Mary Ellen Rumble | 19 December 1905 | The daughter of a farmer in Watervale near Murrumburrah in New South Wales was killed when one of a group of horses attempting to escape from a paddock knocked her down, causing her neck to snap.[251] | |

| L. R. Davis | 1906 | The 76-year-old inmate of the state insane asylum in Norfolk, Nebraska, was granted a parole. Upon seeing his grandson, who had come to take him home, "he was so filled with joy that he suddenly expired."[252] | |

| Archibald Anderson | 4 March 1907 | The 19-year-old was bathing in the Yarra River when he choked on a tooth plate.[253] | |

| Jane Hewitt | 1 September 1908 | The woman residing in South Melbourne was found dead on the floor in her nighttime attire, having been unconscious for several days. She died from erysipelas and blood loss caused by a wound to her temple.[254] | |

| Thomas Selfridge |  |

17 September 1908 | Thomas Selfridge and Orville Wright were presenting the 1908 Wright Military Flyer to the US Army Signal Corps Division at Fort Myer. The plane made 41⁄2 rounds around the Fort before running into problems and crashing. Selfridge fractured his skull and died three hours later.<ref name=obit>{{cite news|title=Fatal Fall of Wright Airship; Lieut. Selfridge Killed and Orville Wright Hurt by Breaking of Propeller. Machine a Total Wreck. Increased Length of New Blade and Added Weight of a Passenger Probable Causes. Cavalry Ride Down Crowd Rumor That the Machine Had Been Tampered with Denied by Army Officers—Not Well Guarded.|url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1908/09/18/104755152.pdf%7Cquote=Falling from a height of 75 feet, Orville Wright and Lieut. Thomas E. Selfridge of the Signal Corps were buried in the wreckage of Wright's aeroplane shortly after 5 o'clock this afternoon. The young army officer died at 8:10 o'clock to-night. Wright is badly hurt, although he p |

- ^ Hoff, Ursula (1937). "Meditation in Solitude". Journal of the Warburg Institute. 1 (44): 292–294. doi:10.2307/749994. ISSN 0959-2024. JSTOR 749994. S2CID 192234608.

- ^ a b Elder, Edward (1849), "Menes", in Smith, William (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. 2, Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown – via Google Books.

- ^ "History of Egypt: Book I". History of Egypt and Other Works. Translated by Gillan Waddell, William. Loeb Classical Library. 1940. ISBN 9780674993853 – via University of Chicago.

- ^ Abo Bakr Mohamed, Ahmed (April 2015). "The Assassination of King "Teti": A New Perspective Based on Recent Discoveries and Archeological Evidence". Annals of the Faculty of Arts, Ain Shams University. 43 (April - June (A)): 251–260. doi:10.21608/aafu.2015.6991.

- ^ "Teti".

- ^ "The Ten: Most unusual biblical deaths". record.adventistchurch.com. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita book I

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 14". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 112. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Terpander was an excellent harper, and while he was singing to his harp at Sparta, and opened his mouth wide, a waggish person that stood by threw a fig into it so unluckily, that he was strangled by it.

- ^ Küster, Ludolph (1834). Gaisford, Thomas (ed.). Suidae Lexicon: Post Ludolphum Kusterum ad Codices Manuscriptos Recensuit [Suidae Lexicon: After Ludolph Küster Reviewed the Hand-Written Codices] (in Ancient Greek and Latin). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 1059 – via Google Books.

- ^ Felton, Bruce; Fowler, Mark (1985). "Most Unusual Death". Felton & Fowler's Best, Worst, and Most Unusual. Random House. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-517-46297-3 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brigden, James. "8 strangest deaths of history's ancient rulers". Sky HISTORY. AETN UK. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Murray, Alexander (2007). Suicide in the Middle Ages. Vol. 2: The Curse on Self-Murder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-19-820731-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ McGlew, James F. (1993). Tyranny and Political Culture in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, New York and London, England: Cornell University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8014-8387-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Groebner, Valentin (2002) [2000]. Karras, Ruth Mazo; Peters, Edward (eds.). Liquid Assets, Dangerous Gifts: Presents and Politics at the End of the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages Series. Translated by Selwyn, Pamela E. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8122-3650-7. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Steve (7 August 2019). "20 Unusual Deaths from the History Books". History Collection. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ 国学原典·史部·二十四史系列·史记·卷三十九 [Original Classic of Chinese Studies - Historical Department - Twenty-Four Histories Series - Historical Records] (in Chinese). Vol. 39. Retrieved 6 July 2024 – via www.guoxue.com.

- ^ Gardiner, EN (1906). "The Journal of Hellenic Studies". Nature. 124 (3117): 121. Bibcode:1929Natur.124..121.. doi:10.1038/124121a0. S2CID 4090345.

Fatal accidents did occur as in the case of Arrhichion, but they were very rare...

- ^ Matlock, Brett; Matlock, Jesse (2011). The Salt Lake Loonie. University of Regina Press. p. 81.

- ^ a b "Gruesome, bizarre, and some unsolved: 44 of the most unusual deaths from history". Weird. mru.ink. 30 September 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Valerius Maximus. "Book IX, chapter XII. Of Unusual Deaths". Factorum et dictorum memorabilium libri IX. Translated by Speed, S. Retrieved 5 September 2024 – via Attalus.org.

But not to digress any further, let us mention those who have perished by unusual deaths.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 7". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 111. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Milo, the Crotonian, being upon his journey, beheld an oak in a field, which somebody had attempted to cleave with wedges; conscious to himself of his great strength, he came to it, and seizing it with both hands, endeavoured to wrest it asunder; but the tree (the wedges being fallen out) returning to itself, caught him by the hands in the cleft of it, and there detained him to be devoured with wild beasts, after his many and so famous exploits.

- ^ Copeland, Cody (10 February 2021). "The Bizarre Death Of Milo Of Croton". Grunge.com. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

Milo of Croton's death was bizarre, but fitting

- ^ a b c d e f g Marvin, Frederic Rowland (1900). The Last Words (Real and Traditional) of Distinguished Men and Women. Troy, New York: C. A. Brewster & Co. Retrieved 5 January 2022 – via Google Books.

To some of the most distinguished of our race death has come in the strangest possible way, and so grotesquely as to subtract greatly from the dignity of the sorrow it must certainly have occasioned.

- ^ Bark, Julianna (2007–2008). "The Spectacular Self: Jean-Etienne Liotard's Self-Portrait Laughing".

- ^ Burkert, Walter (1972). Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Simoons, Frederick J. (1998). Plants of Life, Plants of Death. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 225–228. ISBN 978-0-299-15904-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Zhmud, Leonid (2012). Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans. Translated by Windle, Kevin; Ireland, Rosh. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 137, 200. ISBN 978-0-19-928931-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 30". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 114. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Anacreon, an ancient lyric poet, having outlived the usual standard of life, and yet endeavouring to prolong it by drinking the juice of raisins, was choaked with a stone of one that happened to fall into the liquor in straining it.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Anacreon". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 906–907.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 6". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 111. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Heracl[t]ius, the Ephesian, fell into a dropsy, and was thereupon advised by the physicians to anoint himself all over with cow‑dung, and so to sit in the warm sun; his servant had left him alone, and the dogs, supposing him to be a wild beast, fell upon him, and killed him.

- ^ Fairweather, Janet (1973). "Death of Heraclitus". p. 2. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017.

- ^ a b Thucydides I, 138 Archived 2008-04-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Marr, John (October 1995). "The Death of Themistocles". Greece & Rome. 42 (2): 159–167. doi:10.1017/S0017383500025614. JSTOR 643228. S2CID 162862935.

- ^ Plutarch Themistocles, 31 Archived 2008-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Diodorus XI, 58 Archived 2008-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aristophanes 84–85 Archived 2015-06-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pliny the Elder. "chapter 3". Naturalis Historiæ. Vol. Book X.

- ^ La tortue d'Eschyle et autres morts stupides de l'Histoire [Aeschylus' tortoise and other stupid deaths in history] (in French). Editions Les Arènes. 2012. ISBN 978-2352042211.

- ^ a b c d McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e Elhassan, Khalid (4 July 2018). "10 Historical Deaths Weirder Than the Movies". History Collection. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Paoletti, Gabe (31 July 2019) [Originally published 13 November 2017]. Kuroski, John (ed.). "The Strange Deaths Of 16 Historic And Famous Figures". All That's Interesting. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

Many of history's most important figures have suffered strange deaths that do not seem to befit their noble legacy.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wallace, Lorna (13 March 2023). "13 Authors Whose Deaths Were Stranger Than Fiction". Mental Floss. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (2013). The Presocratics and the Supernatural: Magic, Philosophy and Science in Early Greece. New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4725-0416-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Diogenes Laertius, viii. 69 Archived 2017-01-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Meyer, T. H. (2016). Barefoot Through Burning Lava: On Sicily, the Island of Cain – An Esoteric Travelogue. Temple Lodge Publishing. ISBN 978-1906999940. Retrieved 11 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Horace. Ars Poetica. pp. 465–466 – via Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Almagor, Eran (1 August 2018), "Ctesias (b)", Plutarch and the Persica, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 73–133, doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748645558.003.0003, ISBN 978-0-7486-4555-8, retrieved 3 August 2024

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 8". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 111. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Polydamus, the famous wrestler, was forced by a tempest into a cave, which being ready to fall into ruins by the violent and sudden incursion of the waters, though others fled at the signs of the danger's approach, yet he alone would remain, as one that could bear up the whole heap and weight of the falling earth with his shoulders; but he found it above all human strength, and so was crushed in pieces by it.

- ^ Frater, Jamie (2010). "10 truly bizarre deaths". Listverse.Com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists. Ulysses Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-1-56975-817-5 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-19-998212-7 – via Google Books.

Ctesias, the Greek physician to Artaxerxes, the king of Persia, gives an appallingly detailed description of the execution inflicted on a soldier named Mithridates, who was misguided enough to claim the credit for killing the king's brother, Cyrus...

- ^ McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, ix.43 Archived 2017-01-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Diogenes Laertius (1925). "Lives of Eminent Philosophers 6.2. Diogenes". Digital Loeb Classical Library. doi:10.4159/dlcl.diogenes_laertius-lives_eminent_philosophers_book_vi_chapter_2_diogenes.1925. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Preface", Diogenes Laertius: Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Cambridge University Press, pp. ix–xii, 9 May 2013, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511843440.001, ISBN 978-0-521-88681-9, retrieved 6 July 2024

- ^ Suda α 2735

- ^ Baldi, Dino (2010). Morti favolose degli antichi [Fabulous deaths of the ancients] (in Italian). Macerata: Quodlibet. p. 50. ISBN 978-8874623372.

- ^ Jiahui, Sun (1 December 2021). "The Strangest Deaths of Ancient Chinese Rulers". Ancient History. The World of Chinese. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Hubbell, Sue (1 January 1997). "Let Us Now Praise the Romantic, Artful, Versatile Toothpick". History. Smithsonian. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "The Life of Pyrrhus". The Parallel Lives. Vol. IX. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. Loeb Classical Library. 1920. ISBN 9780674991125. Retrieved 6 July 2024 – via University of Chicago.

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, 9.401e.

- ^ Cameron, Alan (1991). "How thin was Philitas?". The Classical Quarterly. 41 (2): 534–538. doi:10.1017/S0009838800004717. S2CID 170699258.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, § 28.

- ^ Wright, David Curtis (2001). The History of China. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-313-30940-3 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Dawson, Raymond, ed. (2007). The First Emperor. Oxford University Press. pp. 82, 150. ISBN 978-0-19-152763-0 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hopper, Nate (4 February 2013). "Royalty and their Strange Deaths". Esquire. Archived from the original on 19 November 2013.

- ^ "This Greek Philosopher Died Laughing At His Own Joke". Culture Trip. 18 March 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Laertius, Diogenes (1965). Lives, Teachings and Sayings of the Eminent Philosophers. Translated by Hicks, R.D. Cambridge, Massachusetts/London: Harvard University Press/W. Heinemann Ltd.

- ^ "The Funniest And Weirdest Ways People Have Actually Died –". visual.ly. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017.

- ^ Dio, Cassius. Roman History, Vol. 40, p. 27. Reproduced in Vol. III of the Loeb Classical Library edition. 1914.

- ^ Mayor, Adrienne. The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithridates. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 166–171.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. "Book 37". Bibliotheca historica. Retrieved 5 September 2024 – via Attalus.org.

He killed himself in a strange and unusual way; for he shut himself up in a newly plastered house, and caused a fire to be kindled, by the smoke of which, and the moist vapours from the lime, he was there stifled to death.

- ^ Cassius Dio, xlvii 49. Appian, Bellum Civile iv 136.

- ^ Church, Alfred J. (1883). Roman Life in the Days of Cicero. London: Seeley, Jackson, & Halliday.

- ^ Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 13". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 112. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Drusus Pompeius, the son of Claudius Cæsar, by Herculanilla, to whom the daughter of Sejanus had a few days before been betrothed, being a boy, and playing, he cast up a pear on high, to receive it again in to his mouth; but it fell so full, and descended so far into his throat, that he was choked by it, before any help could be had.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Tacitus, Annals – Book VI Chapters 28–51". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Ryan, Granger; Ripperger, Helmut (1941). The Golden Legend Of Jacobus De Voragine Part One.

- ^ Cossetta, Erin (12 April 2021). "Here's What An Upside Down Cross Really Means". Thought Catalog. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Lives of the Saints: August: 24. St. Bartholomew, Apostle". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Oil of Saints". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 July 2024 – via www.newadvent.org.

- ^ Il Grande Dizionario dei Santi e dei Beati [The Great Dictionary of the Saints and the Blessed] (in Italian). Vol. 4. Rome: Finegil Editoriale/Federico Motta Editore. 2006. pp. 217–218.

- ^ Catholic Online. "St. Lawrence – Martyr". Archived from the original on 4 January 2018.

- ^ "Saint Lawrence of Rome". CatholicSaints.Info. 26 October 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015.

- ^ Spivey, Nigel Jonathan (2001). Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-23022-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Cayne, Bernard S. (1981). The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 17. Grolier. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7172-0112-9 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Imola". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 July 2024 – via www.newadvent.org.

- ^ Lenski, Noel (2014). Failure of Empire. University of California Press. p. 142.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 9". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. pp. 111–112. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Attila, King of the Huns, having married a wife in Hungary, and upon his wedding night surcharged himself with meat and drink; as he slept, his nose fell a bleeding, and through his mouth found the way into his throat, by which he was choked before any person was apprehensive of the danger.

- ^ a b c d e f g "10 Historical Figures Who Died Unusual Deaths". Medieval. History Hit. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Blackwell. p. 123.

- ^ Monroe, Harriet (1912). Ha Jin on Poet Li Po's Many Names and Deaths.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel; Johnston, William (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 21". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. pp. 112–113. ASIN B001F3H1XA. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918. OL 7188480M. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2024 – via Internet Archive.

Anno Dom. 830, Popiel the Second, King of Poland, careless of matters of state, gave himself over to all manner of dissoluteness, so that his Lords despised him, and call him the Polonian Sardanapalus. He feared therefore that they would set one of his kinsmen in his stead; so that, by the advice of his wife, whom he loved, he feigned himself sick, and sent for all his uncles, Princes of Pomerania (being twenty in number), to come and see him, whom (lying in his bed) he earnestly prayed, that, if he chanced to die, they would make choice of one of his sons to be King; which they willingly promised, in case the Lords of the kingdom would consent thereto. The Queen enticed them all, one by one, to drink a health to the King: as soon as they had done they took their leave. But they were scarce got out of the King's chamber, before they were seized with intolerable pains, and the corrosions of that poison wherewith the Queen had intermingled their draughts; and, in a short time, they all died. The Queen gave it out as a judgment of God upon them for having conspired the death of the King; and prosecuting this accusation, caused their bodies to be taken out of their graves, and cast into the lake Goplo. But, by a miraculous transformation, an innumerable number of rats and mice did rush out of those bodies; which, gathering together in crowds, went and assaulted the King, as he was with great jollity feasting in his palace. The guards endeavoured to drive them away with weapons and flames, but all in vain. The King, perplexed with this extraordinary danger, fled, with his wife and children, into a fortress that is yet to be seen in that lake of Goplo, over-against a city called Crusphitz, whither he was pursued with such a number of these creatures, that the land and the water were covered with them, and they cried and hissed most fearfully: they entered in at the windows of the fortress, having scaled the walls, and there they devoured the King, his wife, and children, alive, and left nothing of them remaining; by which means all the race of the Poland princes were utterly extinguished, and Pyast, a husbandman, at the last, was elected to succeed.

- ^ Walter, James K. (2011). "Ragnars saga loðbrókar". In Gentry, Francis G.; McConnell, Winder; Müller, Ulrich; Wunderlich, Werner (eds.). The Nibelungen Tradition: An Encyclopedia. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-1785-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Le Bas, Philippe (1843). L'Univers, histoire et description de tous les peuples – Dictionnaire encyclopédique de la France [The Universe, history and description of all peoples - French Encyclopedic Dictionary] (in French). Vol. 10. p. 339 – via Google Books.

- ^ Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 461. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Top 10 Strangest Deaths in the Middle Ages". Features. Medievalists.net. 16 July 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Translations of the Orkneyinga saga (chapters 4 and 5), which relates the story, can be read online at Sacred texts Archived 2017-03-29 at the Wayback Machine and Northvegr Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine